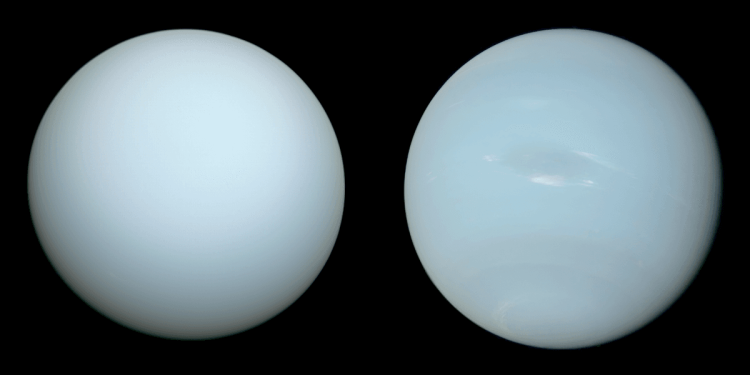

Uranus and Neptune are the two most distant planets in the solar system and have only been visited once by a human spacecraft – by Voyager 2 more than 30 years ago – so there is a lot about them we don’t know. However, one thing we thought we knew was what type of planet it was. Now, a new study wants to question something quite crucial about how we classify them: These worlds, it claims, are not ice giants.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please log in or subscribe to access the full content.

The four “rocky” planets of the solar system – Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury – are small terrestrial planets made of solid rock and metal. The four giant planets – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – are divided into two categories because, although large, they are not identical. The first two are “gas giants” because they are mainly composed of hydrogen and helium, more than 90% by mass. The latter two are known as the “ice giants”. Hydrogen and helium represent less than 20% of the mass of the planets. Uranus and Neptune, on the other hand, are rich in many molecules like water and ammonia that were present in solid ice when the planets formed billions of years ago, models tell us.

For decades, our understanding of the interiors of Uranus and Neptune has relied on what we can glean from their surface features, the behavior of their moons, their magnetic fields, and other indirect means. Which sometimes misled us.

If I were one of those billionaires…floating around with all my money, I would fund two missions: I would fund an orbiter to Uranus and an orbiter to Neptune.

Professor Brian Cox

This new work offers a different way of looking at these outer planets. Instead of modeling the interior of these two worlds based on the potentially flawed information we have, they created random models and then compared them to observational data, creating a catalog of suitable models. They looked at both water- and rock-dominated scenarios and concluded that while planets have this mix of molecules, a rockier internal structure makes more sense with current observations.

“Overall, our results challenge the conventional classification of Uranus and Neptune as ‘ice giants’ and highlight the need for improved observational data or training constraints to break compositional degeneracy,” the authors write in their paper.

So maybe Uranus and Neptune aren’t ice giants; perhaps we have the first “rocky giants” in the solar system. Or another suitable name that doesn’t confuse them with the rocky planets of the solar system. By better understanding what’s going on inside these planets, we can explain their peculiarities, like their magnetic fields, which in the case of Uranus is really weird.

Although the new paper is intriguing, the authors emphasize the need for dedicated missions to Uranus and Neptune to better constrain their properties and even obtain more precise color images.

They are not the only ones who want to revisit these outer worlds. “Really, the case for a big mission, an orbiter to Uranus and Neptune, I think, is so overwhelming! If I was one of those billionaires…floating around with all my money, I would fund two missions: I would fund an orbiter to Uranus and an orbiter to Neptune,” Professor Brian Cox told IFLScience last year.

“With the potential for future missions dedicated to Uranus and Neptune, our method also provides a flexible and unbiased tool for interpreting upcoming data,” the authors write. “Ultimately, the interiors of Uranus and Neptune remain enigmatic, not because they are out of reach, but because the data needed to solve their secrets is still out of reach. Until then, only a plurality of models, not just one, can capture the full extent of the possibilities of their hidden depths.”

The study is accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics and is available on ArXiv.