The prices of the “Liberation Day” announced by US President Donald Trump have one thing in common – they are applied only to goods. Services trade between the United States and its partners is not affected. This is the perfect example of Trump’s particular accent on goods trade and, by extension, his nostalgic but obsolete obsession for manufacturing.

The rehearsal of the Liberation Day continue, with markets around the world. The decision to apply prices on a country basis by country means that the rules on where a product comes is now of central importance.

The stakes to be mistaken could be raised. Trump threatened that anyone trying to avoid prices by moving the supposed origin of a product in a country with lower prices could incur a ten -year prison sentence.

The White House initially refused to specify how it knew the rate levels. But it seems that the rate of each country has been reached by taking the trade deficit of American goods with this country, by dividing it by the value of the exports of goods from this country to the United States, then by revolutionizing it by half, with 10% as the minimum.

It was noted that it is indeed the approach suggested by IA platforms like Chatgpt, Claude and Grok when asked how to create “a uniform playground”.

Economically, the fixing of Trump on goods makes no sense. This point of view is not unique to the president (although it feels it unusually strongly). There is a broader fetishization of manufacturing in many countries. A theory is that it is potentially anchored in human thought by prehistoric experiences of finding food, fuel and a home dominating all other activities.

But for Trump, thought is probably linked to a combination of nostalgia for an age of manufacture (somewhat imagined) and concerns about the loss of quality jobs which provide a solid standard of living in blue passes – an essential part of its political base.

Nostalgia is not a judicious basis for forming economic policy. But the role that emotions play in international affairs have received more attention. It was identified as an “emotional turn” (where the importance of emotion is recognized) in the discipline of international relations.

Of course, this does not mean that the concern about jobs and the unequal effects of globalization are moved. It is clear that the blue passes have suffered in the United States (and elsewhere) in the past 40 to 50 years, the governments giving little attention to the decline.

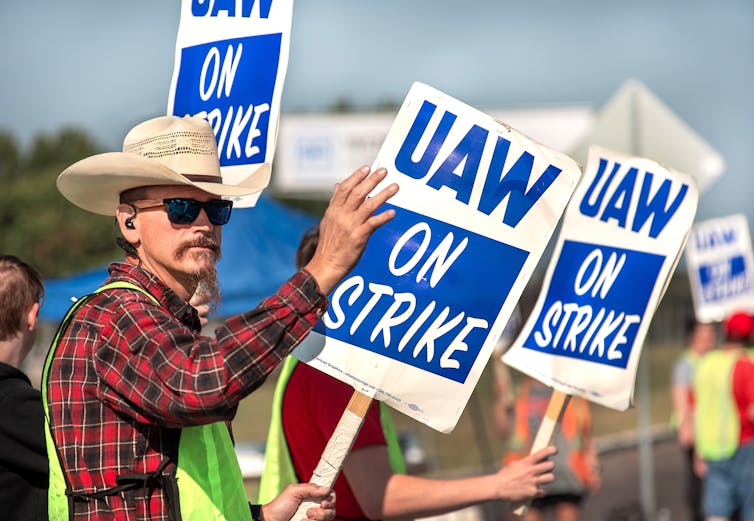

Jon Rehg / Shutterstock

Data on weekly gains in the United States separate by level of education show that wages for those who have no diploma have decreased or stagnated since around 1973, especially among men. It was the cohort that voted disproportionately for Trump. Globalization has created many advantages, especially in the United States, but they tend to be concentrated among the best educated.

Too often, jobs in the service sector that has filled the gap left by the drop in manufacturing have been precarious. This means low wages, low security, a lack of union representation and few possibilities to go up the scale. It is not surprising that there was a backlash.

Unable to go back

So, do Trump’s prices plan to solve this problem? The big tragedy is that there are few reasons to think that they will do so.

The loss of manufacturing jobs partly concerns globalization, which Trump seeks to reverse. But research shows that trade and globalization are often more a scapegoat than a engine, responsible for a small part of job losses (generally considered around 10%).

The main cause of the decline in manufacturing is the increase in productivity. Today, this simply requires fewer people to make goods due to the incessant increase in automation and the associated increase in the quantity of each worker.

If the entire American trade deficit was rebalanced thanks to the expansion of national industries, this would increase the share of manufacturing employment in the United States by approximately one percentage point, from around 8% to 9% depending on figures from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. This will not be transformer.

The effects of prices are also doubled. They will probably return a little manufacturing in the United States-but it could be self-deficit. A greater production of American steel is good for workers, but the higher cost of us in steel feeds us at higher prices for products manufactured with.

This includes the cars that Trump obsessed. Less competitive prices signify a drop in exports and a loss of jobs. The Lord gives and the Lord moves away.

The 1950s were a single period. At the end of the Second World War, the United States was a manufacturing center, representing a third of exports in the world while only taking approximately one tenth of its imports.

There were few other industrialized countries at the time, and they had been flattened by war. The United States alone had avoided this, creating a world of massive demand for American exports, because nowhere else had a significant manufacturing base. It was never going to last forever.

The other point about this period of history is that the economic system had been shaped by colonialism. The European powers had used their position of power to prevent the rest of the world from industrializing. While these empires have been dismantled and the manilles have broken off, these newly independent countries began their own industrialization processes.

As for the United States today, President Trump is wrong if he really believes that the prices will bring a new golden age of manufacturing. The world has changed.