The number of cases of tularemia, an infectious disease, also called “rabbit fever,” has surged in the United States over the past decade, according to a new report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

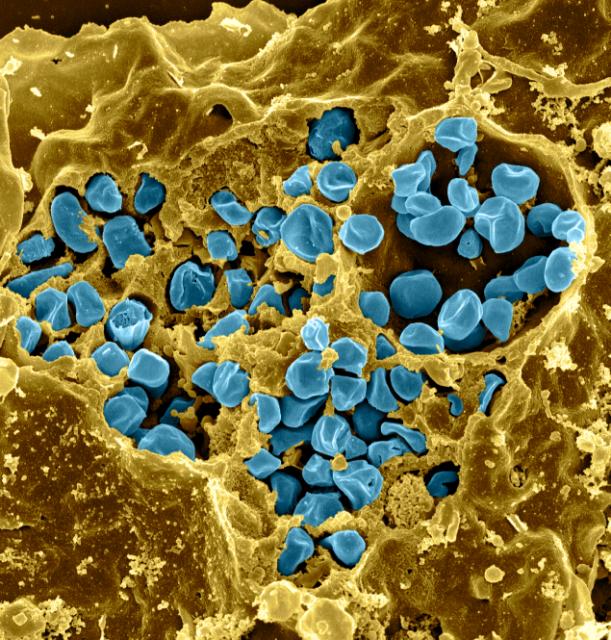

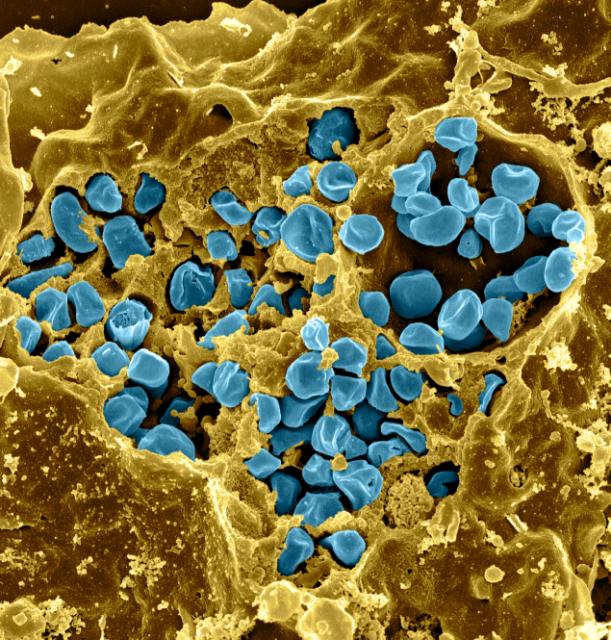

Disease caused by bacteria Francisella tularensiscan be transmitted to humans in numerous ways, including through bites from infected ticks and deer flies, as well as through skin contact with infected rabbits, hares, and rodents, all of which are particularly susceptible to the disease.

But there are much more complicated routes of transmission: mowing the lawn over the nests of animals infected with the disease has been reported to aerosolize the bacteria, thereby infecting the gardener without their knowledge.

This phenomenon was first recorded at a Massachusetts vineyard in 2000, where the resulting tularemia outbreak lasted six months and resulted in 15 identified cases and one reported death.

At least one of the few cases reported in Colorado in 2014 and 2015 was also linked to a lawn mowing incident.

The CDC closely monitors this bacteria, in part because it is classified as a Tier 1 selected agent by the U.S. government due to its bioterrorist potential, and also because even when transmitted naturally, it can be deadly without treatment.

“The case fatality rate of tularemia is generally less than 2 percent, but may be higher depending on the clinical manifestations and the infectious strain,” the report authors note.

Tularemia is relatively rare in the scheme of things: in 47 states, 2,462 cases were recorded for the decade 2011-2022. For comparison, the CDC estimates around 1.35 million cases of Salmonella Bacterial poisonings occur every year throughout the country.

Although these 2,462 cases of tularemia represent only one case in 200,000 people, this is a 56% higher incidence rate than records from 2001 to 2010.

Part of this likely comes from improvements in how we record cases: in 2017, the CDC began including cases where F. tularensis was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based on the number of “probable cases,” which previously included only cases where a person had symptoms, as well as a few molecular markers hinting at the presence of the bacteria.

In addition to symptoms, for a case to be “confirmed”, a sample of the bacteria must be isolated from the infected person’s body, or a massive change in associated antibodies in serum testing will also suffice.

In the 2011-2022 data, there were 984 confirmed cases and 1,475 probable cases. This represents 60 percent of the total cases classified as probable, a considerable change from data from 2001 to 2010, when only 35 percent of cases were classified as probable.

“An increase in reported probable cases could be associated with an actual increase in human infection, improved detection of tularemia, or both,” the CDC team writes. Commercially available laboratory tests also varied during this period, potentially impacting the data.

The incidence among the nation’s First Nations people, as defined by the CDC demographic category “American Indian or Alaska Native,” was about five times higher than among whites.

“Many factors could contribute to the higher risk of tularemia in this population, including the concentration of Native American reservations in the central states and sociocultural or occupational activities that may increase contact with infected wildlife or arthropods,” write the authors of the report.

Others most affected by the disease were children aged five to nine, men aged 65 to 84, and people generally living in the central United States.

Diagnosing tularemia is difficult because symptoms vary greatly depending on the mode of transmission. But better knowledge of these infection routes can help us avoid exposure and help doctors quickly identify and treat disease with antibiotics.

For more details, see the CDC Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report.