There were 56 wild and endangered Puerto Rican parrots living around the El Yunque National Forest before Hurricane Maria in 2017. After the storm, there was only one survivor.

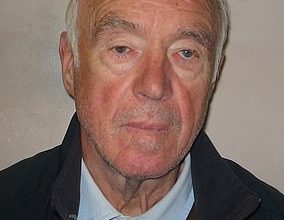

“I admit I cried a few times,” said Tom White, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who has worked for 30 years to reestablish a wild population of Puerto Rican parrots in El Yunque.

The parrot is one of the most endangered birds in the world, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

About 60 years ago, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the parrot as an endangered species, a legal status that has given rise to an ongoing and ambitious effort to rebuild a healthy population of wild birds, which are continues today.

“If human beings are the cause, it’s basically our responsibility to fix it,” White said.

José Sánchez / CBS News

But the Puerto Rican parrot is also one of many species whose habitat and survival are threatened by hurricanes, which are becoming more and more frequent. more and more destructive because of climate change.

Hurricane Maria killed nearly 3,000 people, causing historic floods and landslides. Researchers found Maria extreme precipitation was 5 times more likely due to climate change.

Battered by 175 mph winds, White and his wife rode out the storm in a hurricane shelter with 120 pairs of captive breeding parrots, protecting them from the storm. Then they came out to see the damage.

“We were speechless,” he said. “It went from green and lush to brown and defoliated in a matter of hours.”

All of the captive birds White had in the hurricane shelter survived the storm. But because of the large debris, teams were unable to reach the 56 wild birds that had been released earlier and were living in remote areas of the forest.

While some of these wild parrots were killed by the hurricane’s winds, many others starved to death after the storm, with the island’s forests stripped of vegetation.

“They had nothing to eat,” said Marisel López Flores, head of the parrot recovery program.

Birds in crisis

Birds everywhere are in crisis, and not just exotic birds. Over the past 400 years, nine species of North American birds have gone extinct, according to the National Audubon Society. This century, the group estimates that 314 species are threatened with extinction.

Some of the biggest declines are in the most common types of birds, according to a landmark study from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The study examined population decline between 1970 and 2019 and found significant losses of:

Wood thrushes, found throughout the eastern United States; 60% of them left.

Baltimore orioles, also a bird of the East; two-fifths were lost.

western larks, widespread in the central and western United States; three quarters have disappeared.

Some of the biggest threats to birds come from habitat loss and rising global temperatures. But more intense hurricanes also play a role.

Although many birds are adapted to survive major storms, they may struggle to overcome damage to their habitats needed for nesting, feeding and roosting – which is what happened to many Puerto Rican parrots.

White explained that protecting parrot habitats can also protect the habitats of thousands of other species.

“In doing so, you protect the world for many others at the same time,” he said.

Giving birds a better chance

Since Hurricane Maria, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has successfully reestablished a wild population of parrots, now with a new twist.

Before the hurricane, the birds were released in remote corners of El Yunque. Now, scientists and staff use behavioral techniques that encourage birds to stay near the aviary complex.

Essentially, this combines wild and captive birds into one community in the aviary. In future disasters, this could give birds a better chance of being rescued and fed when the forest is impassable.

Biologists developed this technique in a sister parrot aviary in Puerto Rico, in the Rio Abajo National Forest, where, after Maria, they were able to feed 90 birds and save their lives. Techniques developed in Puerto Rico have also been used successfully in the release of endangered macaws in Brazil.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Tom White said birds survive better with larger flocks.

“Flocks defend themselves against predators and also to better find food resources,” White said.

In January, the El Yunque Aviary released 22 birds from captivity. Between three aviaries across Puerto Rico, there are now about 300 parrots living in the wild, a sign that parrot recovery efforts here are working.

“When I am old and I die, I will be able to say that I did something for my country. This is how I think I contribute to my island,” said López Flores.

Grub5