BBC News

Ngugi wa thiong’o

Ngugi wa thiong’oNgũgĩ wa Thiong’o, died at the age of 87,, was a Titan of modern African literature – a storyteller who refused to be bound by prison, exile and illness.

His work lasted around six decades, mainly documenting the transformation of his country – Kenya – from a colonial subject to a democracy.

Ngũgĩ was to win the Nobel Prize in literature of countless times, leaving the dismayed fans whenever the medal slipped through its fingers.

He will remain in memories not only as a writer worthy of Nobel, but also as a fierce supporter of written literature in indigenous African languages.

Ngũgĩ was born James Thiong’o Ngũgĩ in 1938, when Kenya was under British colonial domination. He grew up in the city of Limuru among a large family of low -income agricultural workers.

His parents climbed and saved to pay for his tuition fees in Alliance, a boarding school led by British missionaries.

In a interviewNgũgĩ recalled his return from the Alliance at the end of the quarter to note that his entire village had been shaved by the colonial authorities.

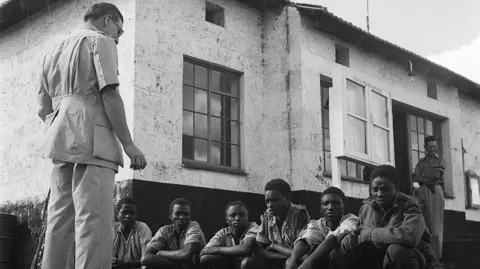

Family members were among the hundreds and thousands of people forced to live in detention camps during a repression against Mau Mau, a movement of independence fighters.

The Mau liftingwhich lasted from 1952 to 1960, touched the life of Ngũgĩ in many devastating ways.

In one of the most overwhelming, Ngũgĩ’s brother, Gitogo, was fatally killed in the back for refusing to comply with the command of a British soldier.

Gitogo had not heard command because he was deaf.

Getty images

Getty imagesIn 1959, when the British struggled to maintain their grip on Kenya, Ngũgĩ left to study in Uganda. He enrolled at the University of Makerere, which remains one of the most prestigious universities in Africa.

During a conference of writers in Makerere, Ngũgĩ shared the manuscript of his first novel with the Vénéré Nigerian author Chinua Achebe.

Achebe transmitted the manuscript to his publisher in the United Kingdom and the book, named Weep Not, Child, was reported on criticism in 1964. It was the first great novel in English to be written by an East Africa.

Ngũgĩ quickly followed with two more popular novels, a grain of wheat and the river between the two. In 1972, the UK Times newspaper said that Ngũgĩ, then 33, was “accepted as one of the exceptional contemporary writers in Africa”.

Then came 1977 – A period that marked a huge change in the life and career of Ngũgĩ. To start, it was the year he became Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and lost his birth name, James. Ngũgĩ made the change because he wanted a name without colonial influence.

He also dropped English as the main language of his literature and swore to write in his mother tongue, Kikuyu.

He published his latest novel in English, Petals of Blood, in 1977.

The previous books of Ngũgĩ had criticized the colonial state, but blood petals attacked the new independent Kenya leaders, representing them as an elite class which had betrayed ordinary Kenyans.

Ngũgĩ did not stop there. The same year, he co-wrote the play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I will get married when I want), which was a hot look at the Kenya class struggle.

His theatrical race was closed by the government of President Jomo Kenyatta and Ngũgĩ at the time was locked in a maximum security prison for a year without trial.

However, it was 12 months fruitful – as Ngũgĩ wrote his first Kikuyu novel, Devil on the Cross, while he was in prison. It is said that he used toilet paper to write the whole book, because he did not have access to a notebook.

Getty images

Getty imagesNgũgĩ was released after Daniel ARAP me replaced Mr. Kenyatta as president.

Ngũgĩ said that four years later, in London for a book launch, He learned that there was a plot to kill him On his return to Kenya.

Ngũgĩ began self-imposed exile in the United Kingdom and then in the United States. He did not return to Kenya for 22 years.

When he finally returned, he received the reception of a hero – thousands of Kenyans turned out to greet him.

But the return was tainted when the attackers broke into the apartment of Ngũgĩ, brutally attacking the author and violating his wife.

Ngũgĩ insisted that the assault was “political”.

He returned to the United States, where he had organized teachers in universities such as Yale, New York and California Irvine.

In the academic world and beyond, Ngũgĩ has become known as one of the main defenders of literature written in African languages.

Throughout his career – and to date – African literature was dominated by books written in English or French, official languages in most countries on the continent.

“What is the difference between a politician who says that Africa cannot do without imperialism and the writer who says that Africa cannot do without European languages?” Ngũgĩ asked in a collection of fundamental and ardent tests, called decoloning of the mind.

In a section, Ngũgĩ called Chinua Achebe – the author who helped launch his career – for writing in English. Their friendship collapsed accordingly.

Far from his literary career, Ngũgĩ got married – and divorced – twice. He had nine children, including four published authors.

“My own family has become one of my literary rivals,” joked Ngũgĩ in 2020 Times interview.

His son, Mukoma wa ngũgĩ, alleged that his mother had been physically mistreated by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

“Some of my first memories are that I will visit her with my grandmother where she would seek refuge,” wrote her son in an article on social networks, to which Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o did not respond.

Later in his life, the health of Ngũgĩ deteriorated. He underwent triple -hearted surgery in 2019 and began to combat kidney failure. In 1995, he received a diagnosis of prostate cancer and gave three months to live.

Ngũgĩ, however, recovered, adding cancer to the long list of difficulties that he had overcome.

But now, one of the lighting lights of African literature – as a Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie once called her – left, leaving the world of a little darker words.

You may also be interested:

Getty Images / BBC

Getty Images / BBC