Xenon gas, like other noble or inert gases, is known to have very few effects. This class of elements, due to its molecular structure, generally does not interact with many chemicals.

But a new study on mice shows a possible use case for xenon: as a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The paper, published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine, shows the potential of inhaled xenon to activate the brain’s immune cells, called microglia, to destroy the plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease and reduce inflammation in the brain. Although the study was conducted in mice, it has already inspired a phase 1 clinical trial, which is currently recruiting patients and expected to start this year.

Most approaches to treating Alzheimer’s disease have focused on targeting beta-amyloid plaques that build up in the brain. Three drugs have been approved in recent years, but these treatments have not proven as effective as researchers hoped, including one, Aduhelm, which has been withdrawn from the market. Some researchers have looked to other targets, such as microglia, as potential alternatives.

The new study “offers a glimmer of hope in this direction, providing a scaffolding on which microglia-focused clinical studies can build to provide a new treatment approach,” said Ifeoluwa Awogbindin, a neuroimmunologist at the University of Victoria in Canada, which was not part of the new study.

Doctors have long used xenon for other purposes: as an anesthetic and to treat brain damage resulting from a lack of oxygen. Some studies had already shown that xenon could protect neurons exposed to a toxic solution in mouse cell cultures. Patrick Pierre Michel, a cell biologist at the Paris Brain Institute who conducted the studies, said the new results are promising and, given previous findings, unsurprising.

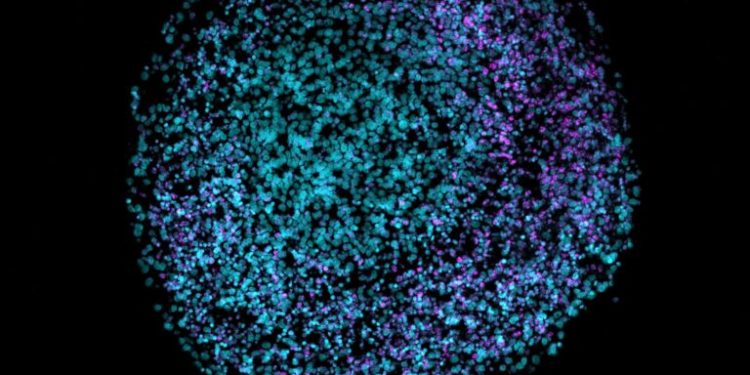

The new study takes cell culture research one step further. The team, from Washington University in St. Louis and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, used a set of different mouse models representing different features of Alzheimer’s disease to show that xenon changes the behavior of microglia, an immune cell found in the spinal cord and brain. During Alzheimer’s disease, microglia have been shown to lose their ability to break down beta-amyloid proteins that accumulate between neurons and damage the brain. But the new study shows that xenon helped microglia regain this ability and also reduced the inflammation that often accompanies Alzheimer’s disease.

In two mouse models expressing hallmark proteins of Alzheimer’s disease, tau and amyloid beta, mice exposed to xenon had lower levels of both proteins. In mice with APOE4 – a genetic variant that increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease – the xenon-treated animals performed better on cognitive tests and showed less brain deterioration.

“This is a really original approach,” said Oleg Butovsky, a neuroimmunologist at Harvard University and one of the authors of the new study. Based on the results, he said the researchers obtained approval from the Food and Drug Administration and their institutional review boards to begin a Phase 1 trial to test the safety of the gas in healthy volunteers.

If the treatment worked in humans, it could provide a relatively simple way to treat the disease, as it would simply require an inhalation device.

“Everything in the paper is wonderful, but the final verdict will be made after a phase 2 clinical trial. If it reaches its end point with a positive effect on biomarkers and cognition, that will be very important,” Butovsky said.