The former member of the Municipal Council of Los Angeles, Nathaniel, “Nate” Holden, has always spoken with a feeling of insurance and a firm belief in his own destiny.

It was the kind of conviction that it took for a black man born in Macon, in Georgia, in 1929 to get into the highest ranks of the political power of Los Angeles – representing the region as a state senator and serving more than 16 years in the municipal council.

An imposing figure in the political arena of Los Angeles, Holden died on Wednesday at 95, his family told the supervisor of the county of Janice Hahn.

“Nate Holden was a legend here in Los Angeles,” said Hahn in a statement. “He was a lion in the state Senate and a force with which it is necessary to count on the municipal council of Los Angeles. I learned a lot sitting next to him in the rooms as a new member of the council. ”

Before launching his political career, Holden was assistant to Hahn’s father, the former County Supervisor of Kenneth Hahn, who relied on Holden for his “unique brand of wisdom”. The young Hahn said that she called him uncle Nate and considered Holden to be part of the family.

Holden was a 6-year-old child in Georgia when, he said, he heard the governor of the state on the radio promising to continue his mission to repress blacks, who at the time was denied the most fundamental human rights and were frequent targets of angry white crowds.

He recalled his childhood distrust to racism which was then fully exposed in the deep south. He threw rocks into local public pools on days when only whites were allowed to use them, and once, a white couple by cleaning their backyard that he intended to become president of the United States.

His father was braking for the center of Georgia Rail Company, and when his parents separated at the age of 10, Nate moved with his mother and brothers to Elizabeth, NJ, where her grandmother lived.

He was a novice boxer at 16, eliminating the experienced competitors and the local champions of his New Jersey Gym. In 1946, he lied about his age and joined the US military. He was deployed in post-Second World War Germany, where he was a military police officer.

When Holden returned to the United States, he decided to become a designer. But, he said, one of his teachers deliberately gave him a bad note to discourage him, telling him that such a job was out of reach for a black man.

When he applied for a training program for military veterans, he was again refused and said that he was wasting his time, that it would never lead to a job.

“I served God and the country, I will enter this training program,” said Holden. “If I don’t understand, I’m going to go to Washington and knock on the door of this president.”

It was finally admitted and studied design and engineering at night while finishing the high school. He finally worked for several aerospace companies, which led him to California.

Holden made his first foray into politics as a member of California Democratic Council, a group of left reform. He lost an offer for the congress after campaigning as opponents of the Vietnam War, but also increased to become president of the Democratic Reform Group.

After being elected to the Senate of California in 1974, he helped write the law on financial discrimination of state housing, which prohibited financial institutions from discriminating according to race, religion, sex or matrimonial state. He also defended legislation to demand that California public schools commemorate Martin Luther King Jr.

Holden left the State Senate after a mandate to appear again for the Congress, losing once again. In 1971, he became deputy deputy deputy of the County Supervisor of Kenneth Hahn, a popular white politician in a strongly black district.

As Holden turned to the Los Angeles Municipal Council in 1987, he had lost six of the seven political campaigns over two decades.

“I don’t think I have never lost a race,” said Holden to Times in 1987. “Maybe I was not elected, but I didn’t lose the race. And each time I ran a race, I think the community has benefited.”

Holden savor the political fight, often to the detriment of his colleagues.

“There is nothing wrong with competition,” he told Times in 1987. “It’s like boxing. If you get up in this ring and you are there by yourself, you are just ShadowBoxing. It’s always good to have a competition. There is nothing wrong with that.”

During the mandate of almost two decades of Holden to the Los Angeles municipal council, he developed a reputation as a lonely and sometimes difficult – abrasive, vindictive wolf and engaging in political greatness. He frequently voted against the rest of the council in unbalanced votes and openly called his colleagues “stupid”, “bars” and “lazy”.

The member of the Council, Joan Milke Flores, told Times in 1989 that she had seen Holden Mark after all those who went against him during a vote of the municipal council, then approach each person on his list to remind them that he would not forget the vote.

“I don’t manage any nursery school,” said Holden. “I ask difficult questions to bureaucrats. Hey, politics is a difficult business. “

When he was forced to leave the council by mandate limits in 2003, Times columnist Patt Morrison said that “a 16 -year -old franchise on scandal and showboating and chutzpah would lose it”.

Among the voters, however, Holden was warmly adopted as an opponent of the political establishment and champion of his community.

Holden represented the 10th black predominance district and became a spokesperson for the poor and the middle class in the South Center and South West of Los Angeles, where the districts fought against drug and gang violence in the late 1980s. He worked to finish funding for an increase in police patrols to reduce crime and promote a more confident relationship between the officers and residents.

He has constantly made tasks lists – -poule nesting corrective, shift in trees, broken lampposts – and the city’s departments peppered with letters and phone calls to roll the work. He became legendary among city employees for having reprimanded them when things did not happen quickly enough.

“They called me stop sign Holden, because I put my district safe for pedestrians,” said Holden. “When something must have been done, I did it.”

He also put pressure for more parks, libraries and leisure centers in his district and was so invested in the districts that when a center of the show arts was built in the middle of the city in 2003, he was appointed in the honor of Holden.

“Nate works harder with her voters and other residents of Los Angeles than to please her colleagues,” said the council at the time, Joy Picus, in Times in 1993. “He has the intelligence of the street and is very populist.”

Always looking for a fight, Holden made a pass to the mayor of the mayor in 1989 against the strongly favored holder, Tom Bradley, who had previously represented the 10th district as a member of the Council.

Holden made a new national during the campaign when he launched a program to take back firearms at the time, offering $ 300 on his own country war chest to all those who make an assault rifle.

Holden lost, but his intense campaign combined with low electoral participation gave Bradley a race for his money.

“He’s a fighter,” said Herb Wesson, who worked as Holden Staff in his first mandate. “If I was in a bar fight, I certainly hope that Nate Holden was on the bar stool next to me.”

The long passage of Holden on the municipal council was partially cemented by its nuptial parade of American Korean voters. Although Koreatown residents did not have a large block of voting, they had a fundraising power, giving a quarter of the campaign contributions that Holden received from 1991 to 1994.

In return, Holden helped owners of American Korean companies to acquire alcohol permits in Los Angeles, transforming the region into one of the city’s hot spots for nightlife after companies failed during an economic crisis in the early 1990s.

“It is the heritage of Nate Holden in Koreatown,” said Charles Kim, executive director of the American Korean coalition, in Times in 2002. “His heritage is many places going from beer and wine in full alcohol license and extending their midnight hours to 2 am”

A Times investigation report later revealed that many business owners who received alcohol licenses had donated the Holden campaigns. And some have seen duplicity in Holden’s efforts since the city councilor so vigorously fought to restrict alcohol permits in southern Los Angeles after the 1992 riots.

Apart from politics, Holden’s tenacity was obvious in other respects, such as the Los Angeles marathon, which he ran at 61 and again at 62. When he ran for an assembly’s seat after the end of his council career, he campaigned while walking in the streets in the district and stopping each block to make an arm.

“I was running every morning in the snow in New Jersey. Cold weather. Before school every morning, I was running,” said Holden. “When I came to California, I ran every morning – 5 am”

Holden’s long career, however, was not without defect. In the 1990s, Holden was struck by three distinct allegations of sexual harassment of the old aids. Women accused him of having touched inappropriate offensive comments and of creating a hostile work environment.

Holden fought aggressively, winning a case in court and adjusting another. A third complaint was abandoned. But his legal defense cost the city about $ 1.3 million.

He has also been sentenced to a fine on several occasions for violating the laws on the financing of campaigns, accumulating more than 70 violations and $ 30,000 in fines. Holden recognized some of the violations, but allegedly alleged that the city’s ethics committee held it at a higher level than its colleagues.

Holden retired from the Council in 2003 but remained active in the community. At 92, he still sits on the board of directors of the South Coast Air Quality Management District, a regulatory agency that oversees air quality for a large part of Los Angeles and the interior empire.

Thinking about his inheritance, Holden said he wanted us to remember him as “a good guy”.

“Do your best for people. Law and order. Make sure people are safe. I have done everything,” said Holden.

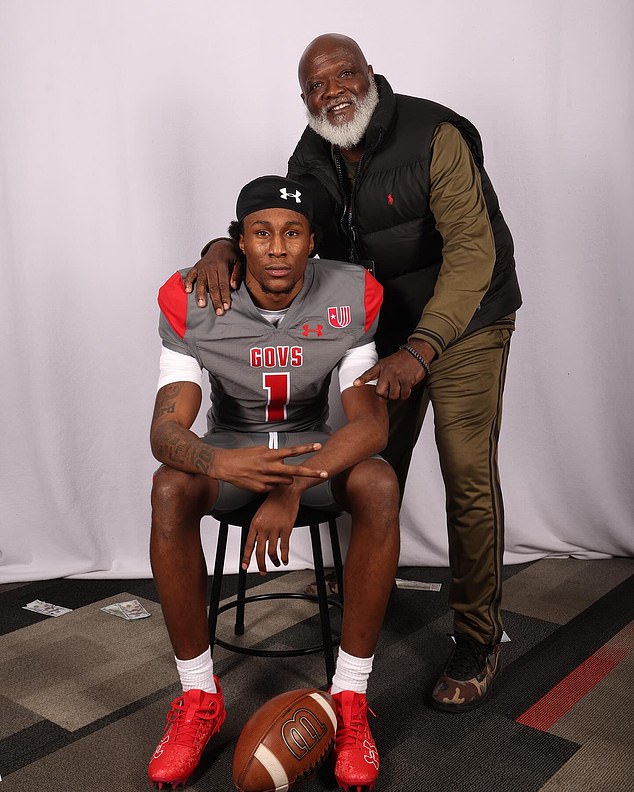

Holden is survived by the sons Reginald Holden, a former Sheriff’s Deputy of the County of Los Angeles, and Chris Holden, a former member of the California assembly and former mayor of Pasadena, as well as several grandchildren. His wife, Fannie Louise Holden, died in 2013 complications from Alzheimer’s disease.

The staff writer Clara Harter contributed to this report.

California Daily Newspapers