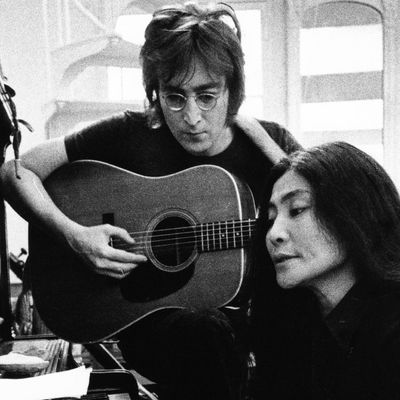

One by one: John and Yoko.

Photo: Magnolia Gralicate Pictures

One by one, the collective name given to the two garden shows of Madison Square interpreted by John Lennon and Yoko Ono during a day in August 1972, constituted the only complete concert that Lennon gave in his post-battering career as a solo artist. He and Ono have been living in New York for a year, getting more and more involved in anti-war demonstrations and a variety of other activist causes (so much so that the Nixon administration would spend several years expelled Lennon). The concert was a kind of gift to their newly adoptive city, arriving shortly after the double album very offbeat Some time in New Yorkwhich was released in June. A live album of the concert itself would have released posthumously in 1986, as well as a complete video of performance.

Images of these shows constitute the vertebral column of the new documentary of Kevin Macdonald, One by one: John and YokoWho could first look like a standard concert film but which turns out to be something quite different. Intercarting swift of reports, advertisements, television programs, contemporary interviews and recently discovered telephone conversations, Macdonald, as well as the Sam Rice-Edwards editor and editor, gives us a swirling journey through what these two artists could have seen and have lived when they tried to navigate their time. There have been a multitude of films related to the Beatles over the years (and we are about to get one more heap), but One by one Cut through the Beatles-Industrial complex to land in the middle of rabies, the confusion, passion and fear of Lennon. By moving away from him in part, he finds him again.

That doesn’t mean that One by one is not also a very good concert document. It is given an IMAX version before its wider theatrical deployment, and the image and its remastered music are worth living on the big screen. But through their juxtapositions, filmmakers also invigorate the songs, many of which had started to feel like shots over the years. We hear that Lennon mentions very early on that he likes to watch television: television, he said, serves him for the same purpose as the chimney did it when he was a child – one thing to look at for hours to spend time. (After all, he had just left the United Kingdom, which had only three channels. American TV, especially in New York, probably made an endless distractions, even at the time.) Macdonald and Rice-Edwards with this idea, presenting their film almost as if the public itself changed the channels, quickly absorbing the textures of life in 1972. Beginning, but the films, but the images may have spoken. When Lennon gives a speech to bring not only the soldiers of Vietnam, but also the equipment (“bringing the machines home, then we will really arrive somewhere”), they cut a colorful extract from The price is correct Announce a new washer and dryer. A telephone conversation on paranoia and listening and sinister figures after Lennon and Ono is followed by reports on the initial break -in of Watergate.

By massaging these connections, MacDonald and Rice-Edwards give us a world whose confusion has pointed out currents, where people and things are more tangled with each other than they seem. The machines, whether bombers or washers, are starting to own us, instead of the opposite. The paranoia which would eventually bring Nixon to fall has already infiltrated in every corner of society. We also have an overview of the notorious “dylanologist” Aj Weberman, a superfann Bob Dylan who felt so betrayed by the popular success of Dylan and turns against the protests he began to track down the singer, searching in his trash to betray his revolutionary products (all the evidence, in the spirit of Weberman, that Dylan was supposed to betray his revolutionary ideals). Even this bizarre relationship echoes the confusion and paranoia of the time, with its uncontrolled consumerism and its feeling that the corporate society now had its own mind, as well as the difficult role that celebrity plays in the whole.

A nuanced image of the relationship of Lennon and Ono emerges by the storm of images. Yoko speaks on the phone about the Chauvin Treatment she has received in recent years Beatles and rupture. She presents herself as the tastiest of the two, a veteran artist specifies in her relations with assistants, colleagues and journalists. Images of a childish John occurring in some of Yoko’s installations sometimes feels like a child with wide -wide eyes at school discovering a new world of activism and experimentation with his new cool, artistic and experienced girlfriend. She leads him, of course, but it is impatient to be led. He is one of the most famous people on the planet – a “monument”, as Yoko herself calls him – but he also seems so frantic, so lost, so impatient to do and mean much more.

There is too much sorrow under the hardened concentration of Yoko. She lost contact with her daughter Kyoko, who was unexpectedly taken by her father; Part of the reason Lennon and Ono had moved to the United States were to be closer to the girl. Ono’s interpretation and tonnitrant of “Don’t worried Kyoko” during the One to One concert is one of the strengths of the film, as is his latest performance of “Looking Over My Hotel Window” during a feminist conference, played on black and white video sequences pixelated from Elle and John, a brutal reverie that suggests the loss of the loss to come.

Yoko’s sorrow to be deprived of his child also feeds the intestinal blow of the last section of the film, when we obtain an additional context on the concert to one. Those who know the event already know it, but the concert came after Lennon and Ono have seen Willowbrook: the last great shameA televised presentation by a young Geraldo Rivera (at the time when he was a real journalist) on the monstrous conditions of the Willowbrook hospital in Staten Island, where children with mental disabled people were forced to live in dirt and agony. One by one was an advantage for these children. The late revelation of the film of that crops the whole concert. This shows how frantic activism, sometimes without rudder, at that time – a prison event here, an anti -war demonstration there – was concentrated and crystallized in this tangible action with enormous real consequences. By helping to cure a little corner of his world, he may have accomplished more than ever before. Therefore, One by one: John and Yoko Not only becomes an extremely moving historical portrait, but a freshly relevant and cathartic portrait.

See everything