- Perceptions of weakness dogged Jimmy Carter’s presidency and legacy.

- Carter inherited a struggling economy and a US military adrift after Vietnam.

- But his administration played key parts in countering the Soviets and rising extremism.

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, the man who received the most credit was Ronald Reagan. The Republican president’s bellicose policies and tough rhetoric — he called it an “evil empire” — were seen as ultimately forcing the Soviets into an arms race they couldn’t afford. And Reagan seemed particularly strong compared to his predecessor, Jimmy Carter.

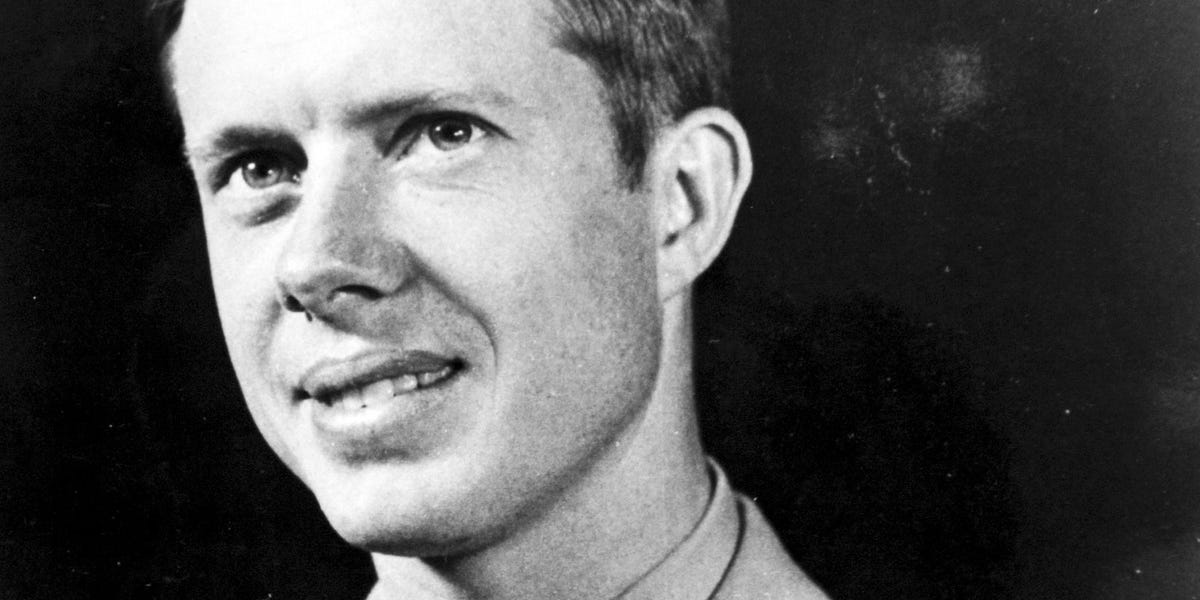

Almost from the start of his Democratic administration in 1977, Carter was criticized for being weak on national security. Never mind that he was an Annapolis graduate who served as a US Navy submarine officer, including being selected for duty on new nuclear-powered submarines. But these perceptions of his supposed weakness bear revisiting after his December 29 death, as Carter played key roles in countering the Soviets and Islamist extremists in the Middle East.

Carter — along with his predecessor Gerald Ford — had the misfortune of inheriting a national security mess. The US military of the late 1970s was called the “hollow force:” Strong on paper but crippled by poor readiness, racial tensions, and unmotivated recruits who dabbled in drugs as the armed forces shifted to an all-volunteer force.

Battered by inflation, soaring gas prices, and the lingering trauma of Vietnam, the American public was not inclined toward more war or defense spending. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union appeared to be at the height of its power, as Moscow fielded new missiles and tanks, and Soviet and Cuban forces intervened in the Angolan Civil War.

Carter entered the White House with a moralist vision of foreign policy, the polar opposite of Richard Nixon’s and Henry Kissinger’s realpolitik. He wanted to emphasize human rights and international cooperation. But like previous high-minded presidents such as Harry S. Truman, he evolved into more of a hawk.

Though he had campaigned in 1976 on a pledge to cut the defense budget, Carter oversaw a defense buildup that by 1980 called for a 14% annual budget increase (actually closer to 5% after inflation). This included new M1 tanks, cargo planes, a new ICBM (the MX, which was eventually canceled), and higher pay for military personnel.

He also canceled what he saw as boondoggles, such as the B-1 bomber. He also ended the controversial neutron bomb project, a small nuclear weapon that produced more radiation than blast, and which detractors saw as the ultimate capitalist weapon (it “seems desirable to those who worry about property and hold life cheap,” warned science-fiction author Isaac Asimov).

In the pre-green energy days of the 1970s, securing the West’s oil supply was paramount. Worried that 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan created a springboard for a Soviet invasion through Iran and Afghanistan to the oil-rich Persian Gulf, Carter laid down the “Carter Doctrine.”

“Let our position be absolutely clear,” Carter warned in his State of the Union address on Jan. 23, 1980. “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”

UPI via Getty Images

The Carter administration created the Rapid Deployment Force, which could be dispatched to any crisis zone in the world (though it was really aimed at the Persian Gulf). On paper, it seemed a powerful force: the 82nd Airborne and 101st Airmobile Divisions, a Marine division and “light” Army divisions, all backed by Navy carriers and Air Force fighter wings. Yet critics questioned how rapid the RDF could be given limited transport capacity, and wondered how lightly armed paratroopers and Marines would fare in the desert against Soviet armor.

Carter sought strategic arms control through the SALT II treaty with the Soviet Union (he asked the Senate not to ratify the treaty after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan). Yet after Moscow deployed SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Eastern Europe, Carter responded by calling for both diplomacy — and US Pershing II missiles to be stationed in Western Europe.

Carter’s critics lambasted his emphasis on human rights, such as the Helsinki Accords, as hopelessly naive. Yet a focus on human rights spurred dissidents, such as the Solidarity movement in Poland, that ultimately weakened the Soviet empire. The Camp David Accords, which brokered peace between Israel and Egypt, dampened Soviet influence in the Middle East and turned Moscow’s former client Egypt into an American ally.

In the end, Carter fell victim to the perception that he was a weak president. His biggest albatross was Iran’s 444-day seizure of the US Embassy in Tehran: even when Carter authorized a risky rescue mission, the botched operation to free 52 Americans failed.

Against a vigorous and masterful communicator like Ronald Reagan, who touted military strength and confrontation with the Soviet Union as more than a necessity but a virtue, Carter appeared lacking. He was defeated by a landslide in the 1980 election.

There were many reasons why the Soviet Union collapsed. The biggest cause was the decrepit Soviet economy; Mikhail Gorbachev and the new generation of Soviet leaders recognized it was not sustainable, but failed to reform it in time.

To say that Jimmy Carter — or Ronald Reagan — were instrumental by themselves in defeating the Soviet Union would be an exaggeration. It is more accurate to say that Carter continued a tradition — dating back to Truman and the early days of the Cold War — of confronting the Soviet threat. Carter doesn’t deserve all the credit, but he deserves his share.

Michael Peck is a defense writer whose work has appeared in Forbes, Defense News, Foreign Policy magazine, and other publications. He holds an MA in political science from Rutgers Univ. Follow him on Twitter and LinkedIn.

businessinsider