Getty images

Getty imagesThe deadly militant attack last week in Pahalgam to the cashmere administered by the Indians, who won 26 civil lives, rekindled a dark feeling of deja vu for the security forces and diplomats from India.

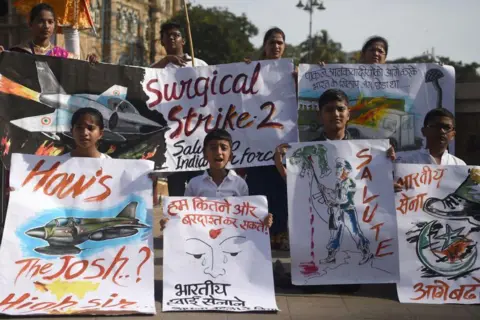

It is familiar land. In 2016, after 19 Indian soldiers were killed in Uri, India launched “surgical strikes” through the control line – the de facto border between India and Pakistan – targeting militant bases.

In 2019, the bombing of Pulwama, which left 40 Indian paramilitary deaths, caused deeply air strikes in Balakot – the first action of this type inside Pakistan since 1971 – reprisal raids and an air fight.

And before that, the horrible attacks of Mumbai in 2008 – a 60 -hour headquarters on hotels, a station and a Jewish center – made 166 lives.

Each time, India has kept militant groups based in Pakistan responsible for attacks, accusing Islamabad of supporting them tacitly – an accusation that Pakistan has always denied.

Since 2016, and especially after the 2019 air strikes, the climbing threshold has changed considerably. The cross -border and air strikes of India have become the new standard, causing reprisals from Pakistan. This has further intensified an already volatile situation.

Once again, say the experts, India finds himself walking on the tightrope between climbing and restraint – a fragile balance of response and deterrence. A person who includes this recurring cycle is Ajay Bisaria, the former High Commissioner of India in Pakistan during the attack on Pulwama, who captured his consequences in his memories, the management of anger: the diplomatic relationship disturbed between India and Pakistan.

Getty images

Getty images“There are striking parallels between the consequences of the bombing of Pulwama and the killings in Pahalgam,” said Mr. Bisaria on Thursday 10 days after the last attack.

However, he notes, Pahalgam marks a quarter of work. Unlike Pulwama and Uri, which targeted the security forces, this attack struck civilians – tourists from all over India – evoking memories of Mumbai attacks in 2008. “This attack bears elements of Pulwama, but much more mumbai,” he explains.

“We are again in a situation of conflict, and the story takes place in the same way,” explains Mr. Bisaria.

A week after the last attack, Delhi quickly moved with reprisal measures: to close the main border crossing, to suspend a keywater sharing treaty, to expel diplomats and interrupt most of the visas for Pakistani nationals – who had days to leave. The troops on both sides have exchanged intermittent shots of small arms across the border in recent days.

Delhi has also prohibited all Pakistani – commercial and military aircraft – of its airspace, reflecting the previous decision of Islamabad. Pakistan retaliated with its own visa suspensions and suspended a 1972 peace treaty with India. (Cashmere, claimed in whole by India and Pakistan, but administered by parties by each, has been a flash point between the two nuclear nations since their score in 1947.))

Ajay Bisaria

Ajay BisariaIn his memoirs, Mr. Bisaria recounts India’s response after Pulwama’s attack on February 14, 2019.

It was summoned to Delhi the next day the next day, when the government was quickly moving to stop trade – revoking the status of the most favorable nation in Pakistan, granted in 1996. In the following days, the Committee of the Cabinet on Security (CCS) imposed a 200% customs right on Pakistani products, putting an end to imports and suspended and suspension on the earth Wagah.

Mr. Bisaria notes that a wider set of measures has also been proposed to reduce commitment with Pakistan, most of which were implemented thereafter.

They included the suspension of a cross -border train known as Samjhauta Express, and a bus service connecting Delhi and Lahore; Representation of the talks between the border guards on both sides and the negotiations on the historic corridor of Kartarpur to one of the most sacred sanctuaries of Sikhism, interrupting the broadcast of visas, ceasing to transfer, prohibiting Indian trips to Pakistan and suspending thefts between the two countries.

“As it was difficult to strengthen confidence, I thought. And how easy it was to break it,” wrote Mr. Bisaria.

“All measures to strengthen the expected, negotiated confidence and implemented over the years in this difficult relationship, could be cut on a yellow notepad in a few minutes.”

The force of the Indian High Commissioner in Islamabad was reduced from 110 to 55 only in June 2020 after a distinct diplomatic incident. (It is now 30 after Pahalgam’s attack.) India has also launched a diplomatic offensive.

One day after the attack, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vijay Gokhale, informed the envoys of 25 countries-including the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Russia and France-on the role of Jaish-E-Mohammad (Jem), the militant group based in Pakistan behind the bombardment, and accused Pakistan of using terrorism as a state policy. Jem, appointed a terrorist organization of India, UN, the United Kingdom and the United States, had claimed responsibility for bombing.

AFP

AFPThe diplomatic offensive of India continued on February 25, 10 days after the attack, putting pressure for the designation of the head of Jem Masood Azhar as a terrorist by the United Nations Sanctions Committee and the inclusion on the “list of autonomous terrorists” of the EU.

Although there have been pressure to repeal the industrial water Treaty – a key agreement for the river water sharing – India has rather chosen to retain all data beyond the obligations of the treaties, writes Mr. Bisaria. In total, 48 bilateral agreements were examined for a possible suspension. A multipartite meeting was summoned to Delhi, resulting in unanimous resolution.

At the same time, the communication channels have remained open – including the hotline between the Directors General of Military Operations (DGMO) of the two countries, a key link for military contact in Military, as well as the two high commissions. In 2019, as now, Pakistan said that the attack was an “false flag operation”.

Just like this time, a repression in cashmere saw the arrest of more than 80 “too basping workers” – local supporters who may have provided logistical aid, shelter and information to the activists of the group based in Pakistan. Rajnath Singh, then Indian Minister of India, visited the Jammu-et-Cachemire, and files on the attack and suspicious authors were prepared.

At a meeting with the Minister of External Affairs, Sushma Swaraj, Mr. Bisaria told him that “that the diplomatic options of India deal with a terrorist attack of this nature were limited”.

“She gave me the impression that a difficult action was at the corner of the street, after which I should expect the role of diplomacy to develop,” wrote Mr. Bisaria.

On February 26, Indian air strikes – its first international border since 1971 – targeted the Jem training camp in Balakot.

Six hours later, the Indian Minister for Foreign Affairs announced that strikes had killed “a very large number” activists and commanders. Pakistan quickly denied the complaint. More high -level meetings followed in Delhi.

AFP

AFPThe crisis intensified dramatically the next morning on February 27, when Pakistan launched air -reprisal raids.

In the fighting of dogs that followed, an Indian fighter was killed and his pilot, the commander of the Abhinandan wing Varthaman, ejected and landed at the cashmere administered by Pakistan. Captured by the Pakistani forces, his detention in the enemy territory sparked a wave of national concerns and has further increased tensions between the two nuclear arms neighbors.

Mr. Bisaria writes India has activated several diplomatic channels, with American and British envoys pressing Islamabad. The Indian message was “any attempt from Pakistan to further degenerate a situation or to harm the pilot would cause an climb from India”.

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan announced the release of the pilot on February 28, the transfer of March 1 under the prisoner of the war protocol. Pakistan presented the movement as a “gesture of good will” aimed at dismantling tensions.

On March 5, the dust set up with Pulwama, Balakot, and the return of the pilot, the political temperature of India had cooled. The security cabinet committee has decided to return the High Commissioner of India to Pakistan, reporting an evolution towards diplomacy.

“I arrived in Islamabad on March 10, 22 days after my departure following Pulwama. The most serious military exchange since Kargil had followed his course in less than a month,” wrote Mr. Bisaria,

“India was willing to give older diplomacy another chance … This has reached a strategic and military objective and Pakistan having claimed a concept of victory for its domestic audience.”

AFP

AFPMr. Bisaria described it as a “test and fascinating time” to become a diplomat. This time, he notes, the main difference is that the targets were Indian civilians, and the attack occurred “ironically, when the situation in cashmere had improved considerably”.

He considers climbing as inevitable, but notes that there is also an “instinct of de -escalation alongside the climbing instinct”. When the Committee on the Cabinet on Security (CCS) meets during these conflicts, he says, their decisions weigh the economic impact of the conflict and seek measures which harm Pakistan without triggering a reaction against India.

“Body language and optics are similar (this time),” he says, but emphasizes what he considers the most important decision: the threat of India to cancel the industrial water Treaty. “If India acts on this subject, it would have serious long -term consequences for Pakistan.”

“Do not forget that we are still in the middle of a crisis,” explains Mr. Bisaria. “We have not yet seen a kinetic action (military).”