“Deny, denounce, delay”: The battle over the risk of ultra-processed foods

When Brazilian nutrition expert Carlos Monteiro coined the term “ultra-processed foods” 15 years ago, he established what he calls a “new paradigm” for assessing the impact of diet on health .

Monteiro had noticed that even as Brazilian households spent less on sugar and oil, obesity rates were increasing. The paradox could be explained by increased consumption of foods that have undergone high levels of processing, such as the addition of preservatives and flavorings or the removal or addition of nutrients.

But health authorities and food companies have resisted the link, Monteiro told the FT. “(These are) people who have spent their entire lives thinking that the only connection between food and health is the nutrient content of food… Food is much more than nutrients.”

Monteiro’s food classification system, “Nova”, evaluates not only the nutritional content of foods, but also the processes they undergo before reaching our plates. The system laid the foundation for two decades of scientific research linking UPF consumption to obesity, cancer and diabetes.

Studies of UPFs show that these processes create foods (from snack bars to breakfast cereals to convenience foods) that encourage overeating but can leave the consumer undernourished. A recipe may, for example, contain a level of carbohydrates and fats that triggers the brain’s reward system, meaning more needs to be consumed to maintain the pleasure of eating it.

In 2019, American metabolism specialist Kevin Hall conducted a randomized study comparing people who followed an unprocessed diet to those who followed a UPF diet for two weeks. Hall found that subjects who ate an ultra-processed diet consumed about 500 more calories per day, more fats and carbohydrates, less protein, and gained weight.

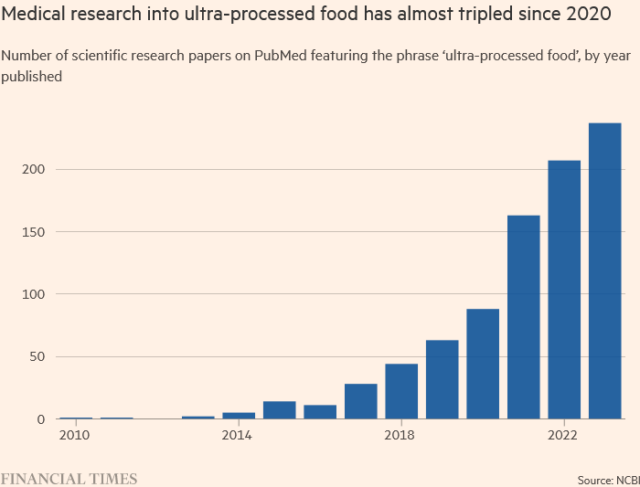

Growing concern about the health impact of UPF has reshaped the debate around diet and public health, giving rise to books, political campaigns and academic articles. It also represents the most concrete challenge to date for the business model of the food industry, for which UPFs are extremely profitable.

The industry responded with a fierce campaign against the regulations. He used some of the same lobbying model as his fight against the labeling and taxation of high-calorie “junk food”: big spending to influence policymakers.

The FT’s analysis of US lobbying data from non-profit Open Secrets found that food and soft drink companies spent $106 million on lobbying in 2023, almost twice more than the tobacco and alcohol industries combined. Spending last year was 21% higher than in 2020, with the increase largely driven by lobbying related to food processing as well as sugar.

Echoing the tactics employed by cigarette companies, the food industry has also tried to avoid regulation by casting doubt on the research of scientists like Monteiro.

“The strategy that the food industry uses is to deny, denounce and delay,” says Barry Smith, director of the Institute of Philosophy at the University of London and a consultant to businesses on the multi-sensory experience of food. food and drinks.

So far, the strategy has proven effective. Only a handful of countries, including Belgium, Israel and Brazil, currently refer to UPF in their dietary guidelines. But as the weight of evidence on UPFs grows, public health experts say the only question now is how, if at all, it will be translated into regulation.

“There is scientific agreement on the science,” says Jean Adams, professor of food public health at the MRC Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge. “It’s about how to interpret that to make policy that people aren’t sure about.”

News Source : arstechnica.com

Gn Health