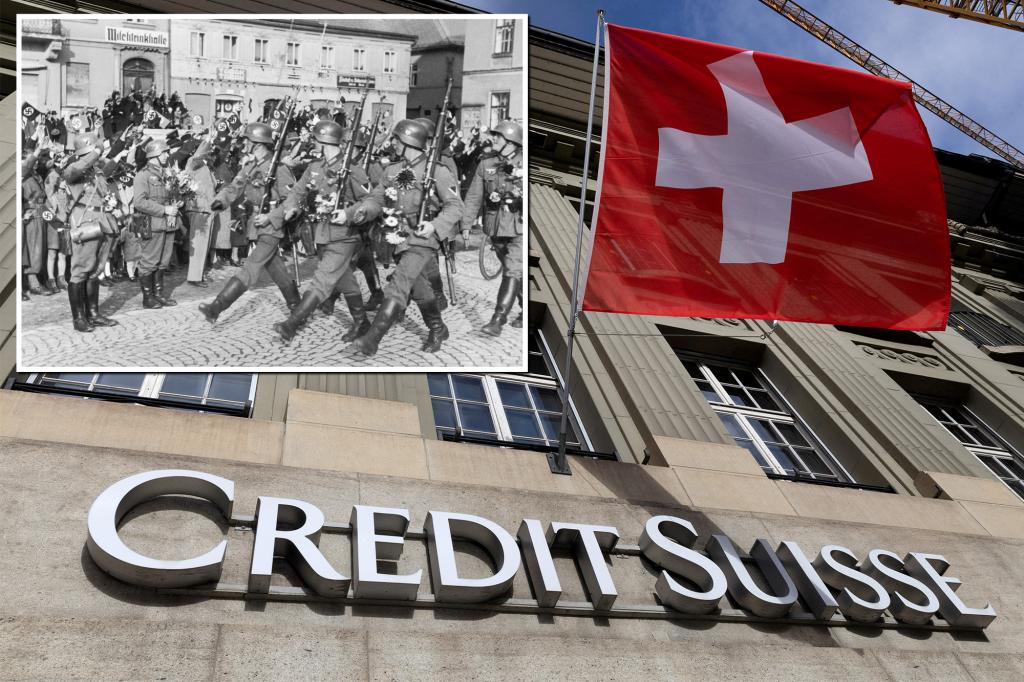

Swiss bankers sought to cover up the extent to which they helped the Nazis store looted assets during World War II by placing their account information under a secret file with the stamp “American blacklist,” according to a report.

Investigators digging into archives at failed lender Credit Suisse found several Nazi-linked bank accounts that were never disclosed during 1990s-era probes that led to a $1 billion restitution agreement with survivors of the Holocaust, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Researchers digging into records also found evidence of an account that was controlled by senior Nazi SS officers and a Swiss intermediary that was believed to have been used to move and store looted assets, the Journal reported.

Credit Suisse maintained bank accounts that were controlled by known Nazis — the details of which were meant to be concealed from investigators as they were stamped with the term “American blacklist,” according to the Journal.

Some of those accounts were used by business entities that seized Jewish-owned assets and relied on forced labor at concentration camps, investigators learned.

The latest investigation was conducted by former federal prosecutor Neil Barofsky, who is currently a partner at Manhattan-based law firm Jenner & Block LLP.

In 2021, Credit Suisse hired Barofsky to conduct an independent investigation after the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish human rights organization, flagged evidence of possible Nazi-linked accounts that were not disclosed.

During the course of his investigation, Barofsky accused Credit Suisse bankers of failing to adequately cooperate.

After Credit Suisse fired Barofsky a year into his work, he authored a report which alleged that senior Nazi commanders who fled to Argentina after the war maintained accounts with the bank as recently as 2002.

In late 2023, Barofsky was reinstated by UBS after the bank acquired Credit Suisse in an emergency rescue.

After Barofsky was removed from the probe, the Senate Budget Committee, which has jurisdiction over the State Department’s Office of the Special Envoy for Holocaust Issues, accused Credit Suisse of failing to fully probe the allegations brought up by the former prosecutor.

“While Credit Suisse initially agreed to investigate evidence of previously unidentified Nazi-linked accounts, the information we’ve obtained shows the bank established an unnecessarily rigid and narrow scope, and refused to follow new leads uncovered during the course of the review,” Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), the top Republican on the panel, wrote in April 2023.

Last month, Barofsky wrote a letter to the US Senate indicating that UBS and Credit Suisse provided full access to their archives and that a team of more than 50 people had been assigned to look into the details.

“The investigation has identified scores of individuals and legal entities connected to Nazi atrocities whose relationships with Credit Suisse had either been previously unidentified, or for which the relationship had been partially identified but the full nature of the bank’s involvement has not yet been reported publicly,” Barofsky wrote in the letter.

Switzerland, which has a long-standing policy of maintaining neutrality in conflicts, has historically been known as a banking hub due to its strict laws governing secrecy and confidentiality.

In 1998, Credit Suisse and other Swiss banks agreed to a $1.25 billion settlement to compensate Holocaust victims and their heirs for stole assets deposited before and during WW II.

“UBS is committed to contributing to a fulsome accounting of Nazi-linked legacy accounts previously held at predecessor banks of Credit Suisse,” a bank spokesperson told the Journal.

New York Post