Scientists are increasingly concerned that infections with the SARS-CoV-2 virus could trigger more cases of chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS).

A new study found that six months or more after SARS-CoV-2 infection, participants were 7.5 times more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS than those who had not been infected .

“Our results provide evidence that the rate and risk of developing ME/CFS after SARS-CoV-2 infection are significantly increased,” write the study authors, led by ME/CFS researcher Suzanne Vernon. SFC, from the Bateman Horne Center in the United States. .

Their findings, the researchers add, “are supported by other studies that have implicated infectious agents such as Epstein-Barr virus and Ross River virus and non-viral diseases such as Q fever and giardiasis in the etiology of ME/CFS”.

Although no one knows what causes ME/CFS, viral infections are thought to be a possible trigger.

Long COVID and ME/CFS share many overlapping symptoms, and some scientists suspect that the two illnesses are somehow linked or triggered by the same factors.

In fact, current estimates suggest that between 13 and 58 percent of people with long COVID meet the diagnostic requirements for ME/CFS.

Before the 2020 pandemic, the health burden of ME/CFS in the United States was estimated to be twice that of HIV/AIDS.

Now that long COVID has affected more than 18 million adults, some researchers predict we could face twice as many cases of ME/CFS in the near future.

The current study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and included 11,785 participants who had had COVID-19 at least six months previously and 1,439 uninfected participants.

Importantly, no participants in the analysis had pre-existing ME/CFS and most were vaccinated against COVID-19.

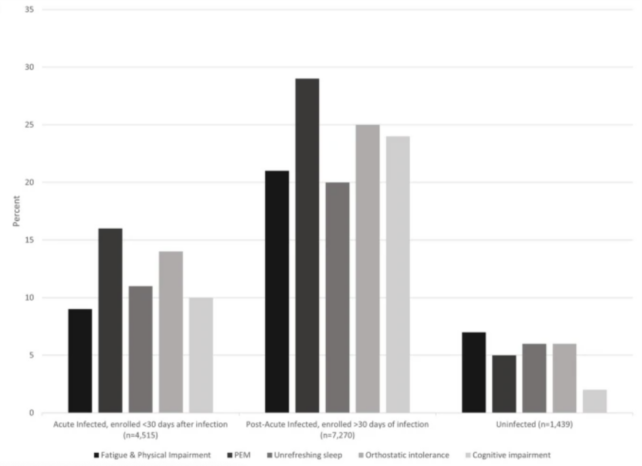

Ultimately, 4.5 percent of participants who fell ill with COVID-19 met the criteria for CFS/ME, which typically requires at least six months of fatigue, accompanied by post-exertional malaise, cognitive impairment, non-restorative sleep or orthostatic intolerance. .

Of this group, 89 percent also met criteria for long COVID.

This may indicate that ME/CFS after COVID-19 “represents a critically ill subset” of long-term COVID patients, the authors hypothesize. But more research is needed to disentangle these two diagnoses, especially since both diseases are highly variable from patient to patient.

While 4.5 percent may not seem like much, it’s several times higher than the pre-2020 rate. Additionally, nearly 40 percent of infected participants were considered “ME/CFS type,” which which means they had at least one ME/CFS symptom six months later. after COVID-19.

In comparison, only 0.6 percent of uninfected participants met the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, and 16 percent of them had only one symptom.

Post-exertional malaise, or worsening of symptoms after exercise, was the most common symptom reported by all participants with ME/CFS.

Orthostatic intolerance, where standing leads to low blood pressure and elevated heart rate, was the second most common symptom.

Long COVID, meanwhile, tends to be marked by lingering symptoms of COVID-19 itself, like breathing problems or chest pain.

“Compared to those who never met criteria for ME/CFS in the infected cohort, those with post-COVID-19 ME/CFS were more likely to be white, female, between 46 and 65 years of age , and to live in a rural area, and less likely to have been vaccinated at the time of registration and to have completed their university studies, “explain Vernon and his colleagues.

Understanding why some people are more susceptible to long COVID or ME/CFS could help researchers find new avenues for prevention and treatment of both diseases.

Since neither has a known cause or cure, and both are on the rise, there’s every reason to keep digging.

The study was published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.