Belarusians will head to the polls this weekend to vote in a presidential election that will almost certainly see incumbent Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko return to power for a seventh time.

The country was rocked by the largest mass protests since independence during the previous massively falsified elections in August 2020, where Lukashenko won a landslide victory according to the official count, but lost decisively to the leader. Belarusian opposition Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, according to the few rebel polling stations. which published the actual vote count. The protest continued for the rest of the year, until freezing winter weather reduced the size of the crowd to the point where Belarusian security services were finally able to regain control of the streets.

The former collective farm manager has learned his lesson and is expected to run unopposed in these elections, with the exception of a few hand-picked straw men to give the election a veneer of legitimacy. Lukashenko’s regime carefully conducted a carrot-and-stick electoral campaign, raising the minimum wage and pensions of state-owned enterprise employees – Lukashenko’s main supporters – but at the same time cracking down and carrying out a series of arrests from anyone. in the country likely to protest against the rigged nature of the elections.

Most opposition figures in the 2020 elections have been imprisoned or fled the country into self-imposed exile, including Tikhanovskaya, who now lives in Latvia with her children, while her husband Sergey Tikhanovsky languishes in a Belarusian prison, with an estimated number of people. Another 1,300 political prisoners, according to the Viasna Human Rights Center.

Farmer turned president

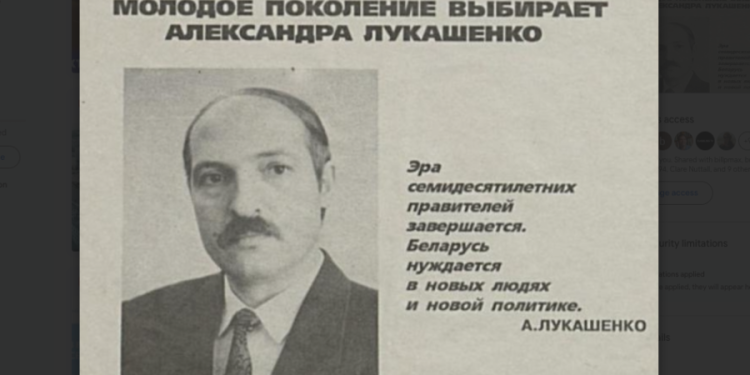

Lukashenko has now been in power for 30 years and was first elected in 1996, when he ran on an anti-corruption agenda and won the election – a rare example of a changing of the guard among countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). In almost all of the 15 newly created republics, leadership was taken over in 1991 by whoever was leading the former Soviet Socialist Republic at the time, and in most countries that leader remained president for the next decade or more.

However, once in power, Lukashenko quickly consolidated his grip on power and later amended the 1996 constitution to remove the two-term limit, effectively becoming president for life, if he so desired.

He has talked about quitting his job, under Russian pressure to resign and hand over to new blood. Last year, he strengthened the All-Russian People’s Assembly (ABPA), once a purely consultative body, and gave it real constitutional powers. Analysts believe he could resign, but take over the leadership of this body in order to fulfill his promise to leave the country, while remaining in power. He also appears to be grooming his son Kolya to succeed him when he retires.

Carrot campaign

The state provided benefits to loyal voters in the form of wage increases and larger pensions. The main beneficiaries are its ultra-loyal security forces, senior civil servants and state sector leaders, which the regime also uses as a political tool to monitor and control the population.

Just before the start of voting, Lukashenko ordered the release of 23 more political prisoners on the eve of the vote, according to a January 18 government press release.

It was the ninth round of prisoner releases over the past year in a sign of public clemency. In total, some 230 political prisoners have been released over the past year as part of an effort to portray Lukashenko as a benevolent leader, but none of the main opposition leaders who actually challenged his rule during the 2020 elections, in particular Viktor Babariko. , Sergei Tikhanovsky or Maria Kolesnikova – were released.

One of the few advantages Lukashenko has to offer has been a boom in consumption over the past three years, as the fallout from the Kremlin’s massive military spending flows across the border to Belarus’s myriad industrial factories.

The economy grew by 4% in 2024, while real household disposable incomes increased by 9.5% and real wages climbed by 12%. As of November 2024, the average salary exceeded 2,200 BYN ($673), a relatively high salary in the CIS. Overall, average wages have risen by a quarter since the start of the war in Ukraine, with wages pushed up by the same labor shortages plaguing Russia. Unlike Russia, inflation was a modest 5.2%, remaining within the 6% ceiling set by the National Bank of the Republic of Belarus (NBRB). And exports to Russia are booming, expected to reach some $50 billion for all of 2024.

Although there are few private business or national fortune stories (apart from the once-thriving IT sector), Lukashenko has managed to maintain stable, cradle-to-grave support from the era Soviet. and services. This is the basis of his support among working-class factory workers.

However, the outlook for 2025 is not as good as the Russian economy cools as war-related distortions of the economy begin to take their toll, bringing Belarus down with it. The Belarusian economy remains heavily subsidized by access to cheap Russian energy.

Stick campaign

The crushing repression that came into force following the 2020 protest has intensified and the unreformed KGB (Belarus is the only country in the former Soviet Union not to have renamed the security service from the era Soviet) is waging a campaign of intimidation.

Following the mass protests, the entire independent press was shut down and what little tolerance for liberalism was crushed. Since 2020, the regime has eliminated all but four loyal political parties and liquidated more than 1,800 civil society organizations.

Lukashenko was nearly ousted following a disastrous speech to workers at the MZKT factory, which makes military trucks, in August 2020. In theory, his most loyal supporters, the truck factory workers booed and heckled Lukashenko, visibly disconcerted, who quickly left the country. the plant. This could have been his Ceausescu moment until Russian President Vladimir Putin stepped in and said Russia would provide Minks “what they need” to maintain order – widely understood as a military force.

Since then, Lukashenko, who remains deeply unpopular, has relied almost entirely on the support of the security services to maintain his grip on power.

Candidates

Early voting began on January 21 as students and public sector workers were bused to polling stations. They must choose between Lukashenko and the four other candidates – Aleh Haidukevich, Alexander Hizhnyak and Siarhei Syrankou – who have been allowed to enter the race. International election observers, such as the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), were not invited to observe the elections.

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) rapporteur Ryszard Petru said the election lacked debate, free choice and transparency and therefore “cannot and will not meet the standards internationally recognized fairness and legitimacy.

A poll from the Chatham House Belarus Initiative suggests that the number of people planning to vote in these elections has fallen by half compared to 2020, THE Independent from Kyiv reports. Pro-government polls predict that 61% of respondents intend to participate in the January 26 vote, while only 11% of the protesting public is ready to vote.

In a sort of political gamble, Lukashenko allowed a fourth candidate, Hanna Kanapatskaya, to be placed on the ballot as a “real” symbolic opposition candidate, with the aim of allowing those disappointed by the Lukashenko regime to let off steam and legitimize the elections.

Kanapatskaya continues to position herself as a supporter of “national-democratic values” and has unexpectedly won the support of the democratic branch of the Belarusian Communist Party. However, even if she is not a classic pigeon, she is unlikely to become the epicenter of a political challenge to Lukashenko’s authority.

The opposition in exile, powerless to act

The exiled opposition decided not to act in these elections, preferring to continue its pressure campaign on its European allies to step up pressure on the Lukashenko regime. And his attempt to cling to power was made easier by intensifying infighting among opposition leaders, which grew stronger throughout the year.

The Belarusian opposition, led by Tikhanovskaya, is increasingly frustrated by the lack of progress and is divided over the best strategy to proceed with the release of political prisoners. Tikhanovskaya wants to stick to the “all or nothing” tactic of getting help from Europe to force Lukashenko’s hand.

Others prefer a “piecemeal” approach of trading sanctions relief in exchange for prisoner releases – something the Lukashenko regime has also encouraged. Opposition veteran Zianon Pazniak publicly condemned Tikhanovskaya’s cabinet’s approaches aimed at isolating Lukashenko’s regime.

Infighting among exiled leaders has intensified to the point that Tikhanovskaya’s leadership role has become visible, but so far her prominence on the international stage has left her in charge. But advocates of de-escalation in relations with Lukashenko’s regime have been unable to form a stable alliance or directly challenge Tikhanovskaya’s leadership.

Although Tikhanovskaya’s Coordination Council has managed to increase its engagement with European partners, notably the Council of Europe and the Polish authorities who now lead the Council, divisions persist over strategy. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk has promised to put Belarus at the top of the agenda during Poland’s EU presidency which began on January 1.

The opposition also hoped to undermine Lukashenko’s legitimacy with his “New Belarusian Passport” program, due to be launched this month, under which the government in exile issues passports to exiles. But as no partner country wanted to recognize the passports, the project failed and, combined with unseemly bickering, further weakened the opposition’s credibility.

The European Parliament plans to adopt a special resolution regarding the 2025 elections, which is expected to condemn the falsification of these elections and call for the use of the mechanisms of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to hold Lukashenko accountable. He will also urge EU member states to support an ICC investigation into the situation in Belarus.

Similar resolutions are expected to be adopted by the Polish Senate on January 23-24 and by the PACE on January 27-31.