Back-to-back wet years in Los Angeles set a rainfall record

After a relatively dry fall in Southern California, there was a point last December when it seemed that fears of a strong, wet El Niño winter may have been overblown.

So much for that.

Within weeks, a succession of powerful storms turned the tide, dumping a flood of intense, record-breaking precipitation across California, much of it in the southwest region of the state.

This wet trend continued as winter gave way to spring, with last weekend’s storm dumping up to 4 inches of rain in some areas, pushing Los Angeles to a new two-year rainfall total never seen since the late 1800s and dashing all hope. for a quick end to the rainy season.

As of Monday morning, downtown Los Angeles had received 52.46 inches of rain in the last two years of water, the second highest amount in recorded history. The only other two-year period from October to September – the so-called Water Year – that saw more rain was between 1888 and 1890, according to the National Weather Service.

“When you look at the records since 1877 in downtown Los Angeles … the second (highest total) is extremely significant,” said Joe Sirard, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard. “We’ve obviously been way, way, way above normal for two years in a row now. For a dry climate like Los Angeles, that’s huge.

And there are probably more on the way. A low-pressure system is brewing off the California coast and expected to move inland later this week, weather officials said, bringing forecasts of above-average precipitation for much of the state until ‘to April 10.

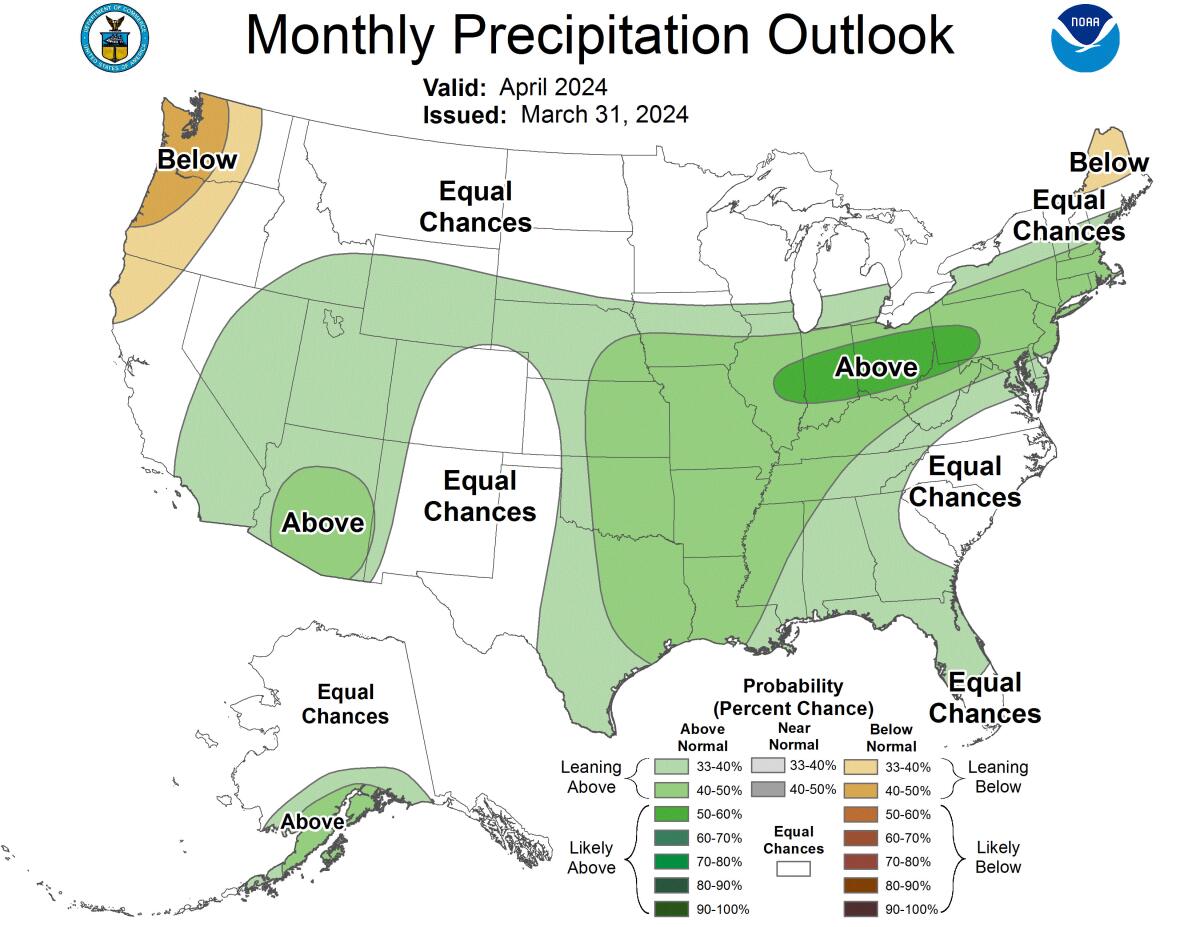

Forecasters also don’t expect this storm to close out the wet season, with long-range forecasts for April favoring slightly above-average precipitation in Southern California, according to the Climate Prediction Center.

“We don’t think it’s the end of the rainy season yet,” said Anthony Artusa, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center. He said a wetter phenomenon was expected to persist through April and perhaps early May, fueled by the last vestiges of an El Niño Southern Oscillation – the tropical Pacific weather pattern that tends to lead to wetter weather in California.

Monthly precipitation outlook published on March 31, 2024.

(NOAA)

The current El Niño phenomenon is shifting towards a more neutral pattern, and a La Niña phenomenon is expected to take over by summer, bringing generally cooler and drier weather. But because the atmosphere tends to lag behind changes in Pacific surface temperatures, Artusa said, “we see an extension of these (El Niño) effects even later, in April.”

Indeed, this year’s soggy winter was in many ways a “canonical” El Niño event — particularly because most storms arrived in late winter and continue into spring, according to Alexander Gershunov, a research meteorologist at UC’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. San Diego.

“The El Niño and La Niña signals usually kick in – when they kick in, because that’s not always the case – in January, February, March, and that’s exactly the part of the year that has been abnormally wet this year,” he said.

However, not all of the wet weather can be attributed to El Niño. Last year’s devastating storms occurred during a La Niña event, and Gershunov noted that some of the state’s wettest years this century occurred during La Niña years, which included also 2011 and 2017.

“In all of these cases, the atmospheric activity of the rivers was extremely strong,” he said. “What we’re finding is that atmospheric rivers don’t always dance to the rhythm of El Niño, and that they can make or break” the classic El Niño pattern.

This latest Easter weekend storm caused highway flooding, brought brief hail and dropped 2 to 4 inches of rain across the region, with some mountainous areas reaching totals closer to 5 inches, according to the weather service . It was far from the strongest storm this rainy season, but it still brought impressive rain totals: 2.1 inches to downtown Los Angeles, 4.67 inches to Lytle Creek, 4.09 near Lynwood, 3.92 in Compton and 3.54 in Stunt Ranch.

The heaviest and most widespread rain fell Friday evening through Saturday morning, setting several daily precipitation records for March 30, including downtown Los Angeles with 1.73 inches, Long Beach with 1.86 inches and in Palmdale with 1.12 inches. Snowfall totals reached 22 inches at Green Valley Lake, 14 inches at Snow Valley and 10 inches at Big Bear City, according to the National Weather Service.

Last month, however, daily precipitation totals more than doubled the records set on March 30 when a deadly atmospheric river storm hit the Southland and much of the Golden State, triggering hundreds of mudslides, flooding and significant destruction. This system dumped 4.1 inches of rain on downtown Los Angeles in one day, making February 4 the wettest day in February history.

This system follows a series of strong storms that brought heavy rain and severe flash flooding to some areas. Most notably, in late December, a month’s worth of rain fell in less than an hour and flooded Oxnard. Then, in January, in San Diego, historic rains filled one-story homes, turned roads into rivers and forced rooftop rescues.

“We had a number of very heavy, high-intensity rainfall events,” Sirard said.

With more rain on the horizon for Southern California, Sirard said he wouldn’t be surprised if this two-year stretch turns out to be the wettest in the City of Angels’ history, as the current tally is less than 2 inches away from the all-time record. , 54.1 inches, decreasing from 1888 to 1890.

“We actually have a really good chance of setting the all-time record,” Sirard said.

Last year became the seventh wettest year in Los Angeles history, with 31.07 inches falling between October 1, 2022 and September 30, 2023. National Weather Service meteorologists consider that 14.25 inches is the region’s normal annual precipitation, bringing last year’s total to more than 200.% on average. With six months remaining, this water year has recorded 21.39 inches, currently the 22nd wettest in recorded history.

This year’s wet winter could also have broader climate impacts, Gershunov said, including potential effects on the upcoming wildfire season. Mountain and forest ecosystems will likely experience fewer fires because snowpack in late winter and spring tends to gradually melt, favoring wetter soils and less combustible vegetation in summer.

On the other hand, abnormal precipitation in coastal ecosystems – like the severe storms that hit Los Angeles and San Diego this winter and spring – encourages the growth of new grasses and other light plants that can fuel the flames. .

“All of this will be dry when the fall wildfire season on the coast arrives with the onset of the Santa Ana winds next October,” Gershunov said.

And while this year appears to be following the El Niño scenario, he noted that the climate model doesn’t always live up to the hype, like the 2015-2016 El Niño, which was touted as a monster event which ultimately produced average precipitation. in California. In fact, measured statewide, precipitation is right around average this year, with 20.9 inches since the water year began Oct. 1, or about 107 percent of the average for that date, according to state data.

With more than 30 million acre-feet of water stored, the state’s reservoirs are at 116% of their historical average. During this time, the snowpack reaches 105% of its April 1 average, when it typically reaches its peak.

“It’s important to realize that ‘average’ precipitation occurs very rarely in California,” Gershunov said. “California’s hydroclimate is volatile: we either have dry years or wet years, and that’s pretty typical. It is very unusual to have an average year in terms of precipitation in California.

Such discrepancies between wet and dry conditions are expected to worsen as climate change upends traditional patterns in the years and decades to come. Global warming is already contributing to shrinking snowpack, in part because warmer storms fall as rain rather than snow.

“We can still have years of very heavy snow, like last year, which had many cold winter storms,” Gershunov said. “But these years should become less and less frequent.”

California Daily Newspapers