When Ray Kohn began experiencing pain in his knees and elbows in 2015, he attributed it to his work as a stuntman and mechanic.

But over the years, he began to notice his body changing in unusual ways: his head grew so much that he needed a larger helmet, and his hands grew so large that he had to resize his alliance three times. His voice changed. His teeth moved in his mouth, creating an underbite. He gained over 100 pounds despite his extremely active lifestyle and was constantly hungry no matter what he ate.

Meanwhile, the pain in his knees and elbows persisted. Cortisone injections, intended to reduce inflammation and pain, never lasted long. In 2019, he underwent the first of three knee surgeries. He would later undergo elbow surgeries. Nothing worked. No doctor he consulted had an answer, even though knee pain forced him to hold on to the wall to walk.

“I was falling apart and I didn’t know why,” Kohn, now 47, said.

Reviewing videos of past stunts showed the extent of the changes.

“I thought, ‘Look how much I’ve changed. I’m not getting old. In fact, I’m transforming.” Why is this happening?

Ray Kohn

In the fall of 2022, Kohn went to a dermatologist after noticing wrinkles forming on his head. The doctor asked to see his hands and commented on their size. Then she examined his tongue, eyebrows and other facial features, and sent him for blood tests which revealed he had abnormally high hormone levels. Those results sent him to Dr. Divya Yogi-Morren, an endocrinologist at the Cleveland Clinic who specializes in pituitary diseases.

“I walked into the clinic room and I looked at him and I already knew what he had, just by looking at him and shaking his hand,” Yogi-Morren told CBS News.

She sought out her colleague, Cleveland Clinic neuroendocrinologist Dr. Varun R. Kshettry, with whom she usually sees patients, because she knew his expertise would also be needed.

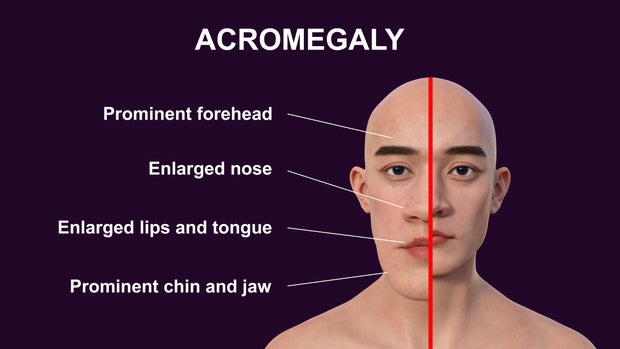

Yogi-Morren and Kshettry said Kohn had clinical features of a condition called acromegaly, a rare condition that causes the body to produce too much human growth hormone. The disease is often caused by a pituitary tumor and brain surgery is the first line of treatment. Wrestler Andre the Giant, who died of congestive heart failure at age 46, also suffered from the disease, which leads to heart complications.

“They said, ‘If you don’t get this out of your brain, you’re going to die. It’s going to kill you,'” Kohn recalled. “And the first thing I asked was, ‘Can I still do stunts after this surgery?'”

What is acromegaly and how is it treated?

Acromegaly is a hormonal disease that occurs when you have too much human growth hormone, said Dr. Alice Levine, an endocrinologist at Mount Sinai who studies acromegaly. Levine was not involved in Kohn’s care. People need large amounts of this hormone as children, but adults need less.

Excess human growth hormone is usually caused by an otherwise benign tumor of the pituitary gland. An MRI revealed that Kohn had such a tumor: His scan found a nine-millimeter mass, almost the same size as the 10-millimeter gland.

In a person with acromegaly, human growth hormone also goes to the liver and binds to receptors there, Levine said. This process elevates a different hormone, called IGF-1, which regulates growth and metabolism in the body.

These two hormones combined led to the symptoms Kohn experienced. Certain parts of the body, especially bones, continue to grow. A person with acromegaly will also experience fluid retention, soft tissue swelling, and other internal problems like prediabetes, cardiovascular complications, and breathing problems like sleep apnea. Other characteristic symptoms include raised lines on the head, large hands and growth between teeth – all symptoms that Yogi-Marren and Kshettry immediately recognized in Kohn.

“He had all the symptoms,” Yogi-Marren said. “He had a symptom in almost every system.”

It took almost 10 years for Kohn to be diagnosed and treated for acromegaly. All three doctors told CBS News this is not unusual. Yogi-Marren estimates that there is typically a “diagnosis delay of about six to 10 years.” Kohn said he was relieved to finally have a doctor who could tell him what was wrong.

Acromegaly can be difficult to diagnose because of the variety of symptoms, Kshettry said, and Yogi-Marren said patients might not realize how much their body is changing.

KATERYNA KON/SCIENTIFIC PHOTO LIBRARY

“From a medical perspective, acromegaly is one of those diagnoses where it takes a village,” Kshettry said. “It’s not a specialty that can really help these patients. We rely on neurosurgery, endocrinology, otolaryngology, dermatology, sleep medicine, orthopedics, dentistry, cardiology – all of these things we need expertise to come together to best care for patients.”

In most patients, once the pituitary tumor is removed, excess production of human growth hormone stops. This also stops the overproduction of the second hormone.

Surgery performed by an experienced surgeon works about 90 percent of the time, Levine estimated. If surgery doesn’t work, a person may have radiation therapy or use medications to shrink the tumor. The disease can recur, Yogi-Marren said, which is why doctors usually do regular follow-ups for several years to make sure hormone levels are normal and there is no new tumor growth. .

Treating conditions caused by acromegaly is another story. Although phenomena such as soft tissue swelling will be reversed once the excess hormones stop, changes to bones and other parts of the body cannot be reversed. A person with acromegaly should undergo corrective surgeries to treat these injuries.

Returning to normal life after surgery

Kohn said he was used to risking his life in dangerous stunts and had “stared death in the face many times”, but the idea of brain surgery had him “scared to death” . It was scarier than previous operations, he said.

“The first thing I asked was if I could still (do stunts) after this brain surgery, and they said, ‘Yes, you can live your life like you’ve never had of operation at all,’ Kohn said.

Knowing it was his best option, he faced his fear and underwent an 8-hour operation in June 2023.

Ray Kohn

The recovery was painful, Kohn said, but his quality of life has improved tremendously since then. He lost more than 100 kilos in just over a year.

Her follow-up appointments were positive, Yogi-Marren and Kshettry said. Typically, they ask the patient to wait about a year after the initial surgery to begin operations to treat long-lasting physical conditions. Kohn is past that mark and expects to undergo double knee surgery and surgery to repair his jaw in the near future.

Kohn said he also spoke to the dermatologist who sent him for additional tests and thanked her for helping save his life. He was also able to participate in several acrobatic jumps where untreated acromegaly would have been impossible.

In doing so, “I felt reborn,” Kohn said. “You know, something was taken away from me that I live to do, that I love to do. Getting back in the car was very special.”