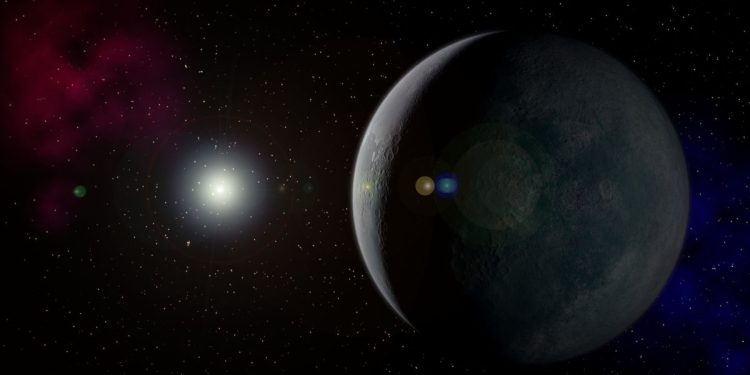

A recently discovered distortion in the outer solar system may have been created by a small rocky world, much closer to the Sun than the Planet Nine hypothesis.

According to a new measurement of the plane of the Kuiper Belt – the vast ring of icy worlds in which Pluto resides – an unexpected 15-degree tilt in the orbital alignment of some objects in the belt could be the result of the influence of a trouble-making planet.

“One explanation is the presence of an invisible planet, probably smaller than Earth and probably larger than Mercury, orbiting in the depths of the outer solar system,” astrophysicist Amir Siraj of Princeton University told CNN.

“This paper is not the discovery of a planet, but it is certainly the discovery of a puzzle for which a planet is a likely solution.”

Related: Scientists discover new dwarf planet in the solar system, far beyond Pluto

It’s actually incredibly difficult to see what lies beyond Neptune’s orbit. So far from the Sun, small objects in the flattened, donut-shaped Kuiper Belt reflect very little sunlight; they are also extremely cold and therefore do not emit thermal (infrared) radiation either.

We know roughly what’s out there, but the details are more elusive. If there are planets beyond Pluto’s orbit about 40 astronomical units, they will not be easy to find. Such worlds would be very small and dark, and if we don’t know exactly what position in the sky they are at any given time, we have no chance of detecting them.

Hope is not entirely lost, however. Neptune was discovered in 1846 after astronomers deduced its location based on the peculiarities of Uranus’ orbit. Pluto was discovered in 1930 after astronomers used the orbital oddities of Neptune and Uranus together to calculate its position. Searching for orbital japery is an age-old method of tracking wayward worlds.

frameborder=”0″allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; write to clipboard; encrypted media; gyroscope; picture in picture; web sharing” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin”allowfullscreen>

As our technology improves, so does our ability to perform a detailed census of the Kuiper Belt, which is believed to extend from about 30 to 50 astronomical units. And if there’s an invisible planet lurking out there all this time, any strangeness in the Kuiper Belt could signal its presence.

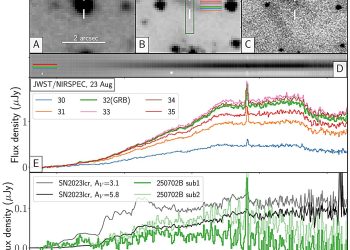

Siraj and his colleagues, astrophysicists Christopher Chyba and Scott Tremaine of Princeton University, designed a new method for calculating the plane of the Kuiper Belt that eliminates the effects of observational bias.

Next, they applied this technique to 154 objects beyond Neptune’s orbit, with semi-major axes between 50 and 400 astronomical units – essentially, objects between the outer edge of the Kuiper Belt and “detached” objects whose orbits are not influenced by Neptune.

If there are no planets nearby, all of these objects should orbit more or less on a flat plane, the researchers explained. Indeed, this is what they found for objects between 50 and 80 astronomical units, and again for objects between 200 and 400 astronomical units.

Sandwiched between these two populations, at distances from the Sun between 80 and 200 astronomical units, Siraj and his colleagues found evidence of a 15-degree tilt relative to the plane of the solar system, with a confidence level of 96 to 98 percent. Tracking simulations also suggest a 2-4% chance that the tilt detection is a false positive.

Now, a distortion of this nature would naturally flatten out in a relatively short period of time – about 100 million years – unless there was something outside keeping it moving. So the researchers ran many-body simulations to see if they could reproduce the effect.

The solar system simulation that came closest to observation was the presence of a small planet, between the sizes of Mercury and Earth, orbiting in the outer solar system with a 10 degree inclination between 80 and 200 astronomical units.

The researchers propose the name “Planet Y” for their hypothetical world.

Of course, this is far from definitive proof, but it gives astronomers a breadcrumb trail to follow in the search for the secrets of the solar system.

With Planet Nine yet to be discovered beyond 400 astronomical units, the outer solar system could be a real treasure trove for future planet hunters. It could even help inform future instrument design.

And that can only be a good thing. Hidden planets or not, learning about the Kuiper Belt and what lies beyond advances scientific understanding of our place in the Universe.

The research was published in the Monthly notices of letters from the Royal Astronomical Society.