BBC News

Family document

Family documentIn January, Lina went to the police.

His ex-partner had threatened her at home in the Spanish town of Benalmádena. That day, he would have raised his hand as if to hit her.

“There had been violent episodes – she was afraid,” recalls Lina Daniel’s cousin.

When she arrived at the police station, she was interviewed and her case recorded with Viogén, a digital tool that assesses the probability that a woman is again attacked by the same man.

VIOGEN – A system based on an algorithm – asks 35 questions about abuses and its intensity, the access of the attacker to arms, his mental health and if the woman has left or plans to leave, the relationship.

He then recorded the threat for her as “negligible”, “low”, “medium”, “high” or “extreme”.

The category is used to make decisions concerning the allocation of police resources to protect women.

Lina was deemed at risk “average”.

She asked for a prohibition order before a specialized court of gender violence in Malaga, so that her ex-partner cannot be in contact with her or share her living space. The request has been refused.

“Lina wanted to change the locks at home, so that she could live peacefully with her children,” said her cousin.

Three weeks later, she died. His partner would have used his key to enter his apartment and soon the house was on fire.

While her children, her mother and her ex-partner have all escaped, Lina did not do so. Her 11 -year -old son was widely reported as saying to the police that it was his father who killed his mother.

Lina’s lifeless body has been recovered from the charred interior of her house. His ex-partner, the father of his three youngest children, was arrested.

Now his death raises questions about Viogen and his ability to ensure the safety of women in Spain.

Viogen did not precisely predict the threat to Lina.

As a woman designated at “average” risks, the protocol is that she would be followed again by a police officer designated within 30 days.

But Lina was dead before that. If it had been “high” at risk, police follow -up would have occurred in a week. Could it have made a difference for Lina?

Tools to assess the threat of repeated domestic violence are used in North America and across Europe. In the United Kingdom, some police forces use Dara (risk assessment of domestic violence) – essentially a control list. And Dash (domestic abuse, harassment, harassment and evaluation of violence based on honor) can be employed by the police or others, such as social workers, to assess the risk of another attack.

But it is only in Spain, an algorithm so closely woven in the practice of the police. Viogen was developed by the Spanish police and academics. It is used everywhere outside the Basque Country and Catalonia (these regions have separate systems, although police cooperation is national).

The head of the family unit and women of the national police in Malaga, CH Insp Isabel Espejo, describes Viogén as “super important”.

“This helps us to follow the case of each victim very precisely,” she said.

His officers treat an average of 10 reports of violence between the sexes per day. And every month, Viogén class nine or ten women as being at an “extreme” risk of repeated victimization.

The implications on resources in these cases are enormous: police protection 24 hours a day for a woman until the circumstances change and the risk decreases. Women evaluated as a “high” risk can also obtain an escort as an officer.

A 2014 study revealed that the officers accepted the viogen evaluation of the probability of repeated mistreatment 95% of the time. Critics suggest that the police have abduced decision -making for women’s safety to an algorithm.

CH Insp Espejo says that the calculation of risk by the algorithm is generally adequate. But she recognizes – even if Lina’s case was not under her command – that something went wrong with Lina’s assessment.

“I’m not going to say that Viogén is not missing – that is the case. But that was not the trigger that led to the murder of this woman. The only culprit is the person who killed Lina. Total security simply does not exist,” she said.

But at the “average” risk, Lina was never a police priority. And did the evaluation of Viogén de Lina had an impact on the court’s decision to refuse her a ban on her ex-partner?

The judicial authorities did not authorize us permission to meet the judge who rejected Lina an injunction against her ex -partner – a woman attacked on social networks after Lina’s death.

Instead, another judge of Malaga gender violence, Maria del Carmen Gutiérrez, tells us in general terms that such an order needs two things: proof of a crime and the threat of serious danger to the victim.

“Viogen is an element that I use to assess this danger, but it is far from being the only one,” she said.

Sometimes, said the judge, she makes the restriction orders in cases where Viogen evaluated a woman as at a “negligible” or “weak” risk. On other occasions, she can conclude that there is no danger for a woman judged at a “average” or “high” risk of repeated victimization.

Dr. Juan Jose Medina, criminologist at the University of Seville, says that Spain has a “postal code lottery” for women who ask for non -compliance orders – some jurisdictions are much more likely to grant them than others. But we do not systematically know how Viogen influences the courts or the police, because studies have not been done.

“How do police and other stakeholders use this tool, and how does they inform their decision-making? We have no correct answers,” he said.

The Ministry of the Interior of Spain has not often allowed academics to access VIOGEN data. And there was no independent audit of the algorithm.

Gemma Galdon, the founder of Eticas – An organization working on the social and ethical impact of technology – says that if you do not check these systems, you will not know if they really offer police protection to good women.

Examples of algorithmic biases elsewhere are well documented. In the United States, the 2016 analysis of a recidivism tool revealed that black defendants were more likely that their white counterparts to be deemed incorrectly judged at risk of repetition. At the same time, white accused were more likely than black defendants to be unjustly reported at low risk.

In 2018, the Spanish interior ministry did not give a green light to a proposal from Eticas to lead a confidential, pro-bono internal audit. So, instead of that, Gemma Galdon and his colleagues decided a viogeni retro-engineer and to make an external audit.

They used interviews with women surviving of domestic violence and information accessible to the public – including data from the judiciary on women who, like Lina, had been killed.

They found that between 2003 and 2021, 71 women murdered by their partners or ex-partner had already reported domestic violence to the police. Those recorded on the VIOGEN system have received “negligible” or “environment” risk levels.

“What we would like to know is that these error rates that cannot be attenuated in any way? Or could we have done something to improve the way these systems attribute risk and protect these women better?” request Gemma Galdon.

The chief of research on the violence between the sexes at the Spanish Interior Ministry, Juan José López-Assorio, is disdainful of the Eticas investigation: this was not done with Viogén data. “If you don’t have access to data, how can you interpret it?” he said.

And it is wary of an external audit, fearing that it would compromise both the safety of women whose cases are recorded and the viogen procedures.

“What we know is that once a woman reports a man and she is under the protection of the police, the probability of additional violence is considerably reduced – we have no doubt about it,” said López -Assorio.

Viogén has evolved since its introduction to Spain. The questionnaire has been refined and the “negligible” risk category will soon be abolished. And even criticism is appropriate that it is logical that a standardized system responds to gender violence.

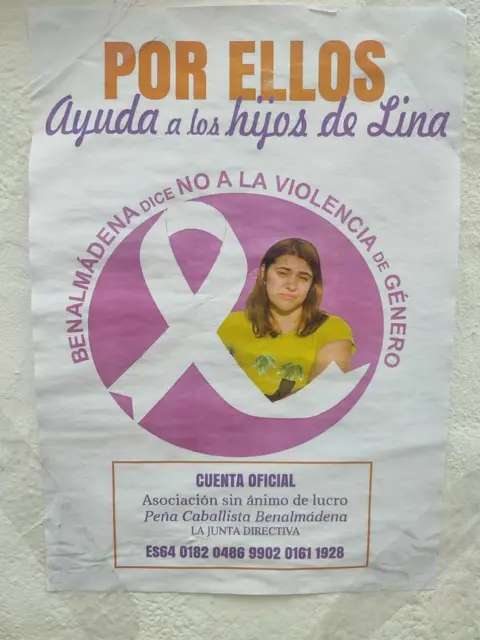

In Benalmádena, Lina’s house has become a sanctuary.

Flowers, candles and photos of saints have been left on the step. A small poster stuck on the wall said: Benalmádena said no to gender violence. The community has collected fundraising for Lina children.

His cousin, Daniel, says that everyone is still in shock from the news of his death.

“The family is destroyed – in particular Lina’s mother,” he said.

“She is 82 years old. I do not think there is something sadder than to have your daughter kills by an attacker in a way that could have been avoided. The children are always in shock – they will need a lot of psychological help.”