The first 30 centimeters of soil are the foundation of life. This in -depth pedosphere slice of the feet is the vital space for most vegetable roots. When the roots go further, it is to anchor the plant, not to nourish it. In this narrow strip, bacteria, mushrooms, nematodes and countless other microscopic organisms form the so-called biological crust, which in turn supports the most of life. Now, a review of thousands of studies – and many other soil samples – reveals that this same 30 centimeters layer also contains toxic metal concentrations in the agricultural soil used to cultivate foods that humans eat. The massive study, published Thursday Scienceestimates that up to 17% of agricultural land worldwide contains excessive levels of one or more metals and metalloids.

A team of researchers from the United States, Europe and China has reviewed thousands of existing thousands of studies on the presence of metals in the soil. They found more than 82,000 papers. After having applied a series of filters – such as focusing on the search for the 21st century, limiting the range to the highest floor layer, and including only studies that have measured metal concentrations in soil samples – they reduced it to around 1,500 studies. These have provided data of nearly 800,000 locations in regions populated around the world.

Using an automatic learning system, an area of artificial intelligence, they have modeled and estimated the global extent of excessive contamination from seven specific metals: arsenic (technically a known metalloid and carcinogen), cadmium (linked to various cancers and subject to accumulate in grains and fruits, in particular rice), chrome (in its heart industry For lithium batteries, and therefore an engine of exploitation and conflict in Central Africa), copper (a natural food component which can disturb the endocrine excess function), nickel (important for plant growth but reign when exaggerated), and lead (harmful for the neurological development of children and cognitive capacities).

Researchers have found that between 14% and 17% of global cultivated land contain dangerously high concentrations of at least one of these metals. In terms of area, the higher estimate represents around 242 million hectares. “We also show that between 900 and 1.4 billion people (around 11% to 18% of the world’s population) live in regions with contaminated soils. It’s a lot of people, ”explains Jerome Nriagu, professor emeritus of environmental chemistry at the University of Michigan and the main study of the study.

It is important to distinguish between contamination and high concentration. “Contamination” generally refers to the pollution caused by humans, such as mines or industrial disasters such as the span of Aznalcóllar. “High concentration”, on the other hand, can come from natural processes – environmental forces (rain, sun, ice, solar radiation …) acting on the pedosphere.

Zoom on the regional level, 19% of China’s agricultural land shows high concentrations of heavy metals, largely linked to pollution caused by humans. Even higher percentages are observed in large parts in the north and center of India. In Europe, the authors rely on data from the Lucas program – an initiative led by the European Commission joint research center to monitor the condition and the evolution of land use through the EU. Based on thousands of soil samples collected periodically, up to 28% of soils in EU member states contain excessive levels of at least one metal. However, these figures reflect the entire land area, not just the land used for agriculture.

Among the metals, the most widely distributed on the map is cadmium, which is present in toxic concentrations in 9% of the soils. It is followed by nickel and chrome, with important concentrations in the Middle East and in northern Russia. Next comes the arsenic, whose distribution rides polluted groundwater areas in large areas of China, but also in several parts of South America. The list ends with cobalt, found at high levels in countries such as Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo – pollution closely linked to mining activities – as well as copper and lead, the most toxic of all, which can cause damage even in small quantities.

“The general distribution of cadmium contamination comes from natural and anthropogenic sources,” explains Deyi Hou, principal of the study and researcher at the Environment School of Tsinghua University in Beijing, in an email. “Geochemically, certain parental rock materials (substrate under the ground), such as black shales, contain high levels of cadmium, leading to high concentrations in the soil due to alteration.”

Anthropogenic activities further aggravate this problem, “in particular the use of phosphate fertilizers containing cadmium, wastewater irrigation, industrial emissions of mining, the merger and treatment of electronic waste, as well as the atmospheric deposit of the combustion of coal”, adds Hou. This combination of pollution caused by humans and natural background level is what is deeply concerned by scientists.

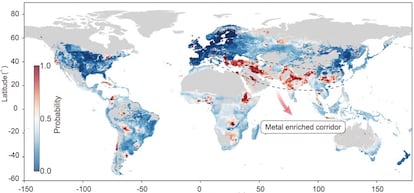

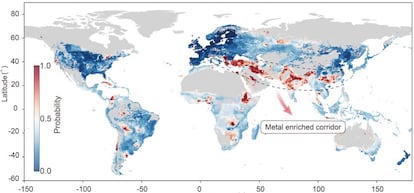

The mapping of the presence of metals (see image) reveals a strip of high concentrations that researchers call the “corridor rich in metals”. This belt extends from northern Italy to the southeast of China, crossing Greece, Anatolia, the Middle East, Iran, Pakistan and the northern and central regions of the Indian subcontinent. These are areas densely populated with deep historical roots, and researchers connect the contamination of today to human activity dating ancient times.

“These regions largely overlap the central areas of precocious human civilizations, in particular ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, Persian culture, ancient Indian societies and the civilization of the Yangtze river in China,” recalls Hou.

Previous work with ice nuclei extracted from Greenland and Siberia have detected abnormal lead concentrations more than 2,000 years. This metal is the key to silver metallurgy.

“While natural factors such as the alteration of parent rocky equipment and phyto extraction (absorption by roots) play a role, millennia of intense human activity, in particular mining and fusion, have been key factors,” explains Hou. “This corridor reflects the lasting heritage of the human impact on the surface of the earth and provides convincing evidence of the anthropocene as a new geological era.”

However, the study does not attribute blame to natural or human causes. It was not its objective, and the selection of the origin of these metals on a global scale is not an easy task. The different time scales involved also complicate the questions. A spill like that of Aznalcóllar, for example, occurred in a few hours on April 25, 1998, while the natural introduction of metals in the pedosphere is a much slower process. The formation of new soils occurs at a rate of only three millimeters per century. Events as progressive as the end of the last glacial period, which took around 10,000 years for the ice to retire, illustrate this contrast. Looking at the map again, it is clear that in areas north of the 50th parallel (which crosses Germany from west to east), there is practically no high concentration of metals.

As a researcher Manuel Delgado Baquerizo of the Spanish Institute of Natural Resources and Agrobiology of Seville (IRNA), “The periods of glaciation have a very strong impact on soil biochemistry; When the ice disappears, the ground disappears completely, leaving the parent rock completely exposed. ” And with the floor goes the metal load.

Delgado Baquerizo, an expert in the environmental impact of soil contamination, stresses that “heavy metals in general are quite toxic, but they have to reach high levels”. “These researchers have examined the soil, not the real food that we could consume,” adds Baquerizo, who was not involved in the study.

For him, the real challenge is to set thresholds – knowing exactly what concentration of a metal per kilogram of soil becomes harmful for the ecosystem of the soil, its inhabitants and human health. “There are no established standards,” he says. The study authors used maximum set limits of 10 different countries and calculated an average – but that does not fully capture the entire scope of the problem.

Baquerizo concludes: “The problem is that many heavy metals have a cumulative effect. You can be exposed to a small quantity, but if you are exposed to this small quantity over a long period, it can have an impact on your health.”

The most obvious example is lead. Since the Romans started using it in their pipes, he continued to be used for over 2,000 years to distribute running water.

Register Our weekly newsletter To obtain greater information coverage in English from the El País USA edition