BBC

BBCShivering a little, Marcos pulls his hoodie over his head as much to protect his identity as to protect himself from the cold.

A year ago, at just 16, he says he was forcibly recruited into a drug cartel in his native state of Michoacán, Mexico.

Recounting his story of horror and escape, Marcos (pseudonym) says he and his family fled Michoacán with only what they were carrying.

One evening, while going to the pharmacy to buy painkillers for his mother’s toothache, he says he was suddenly surrounded by four vans with armed men on board.

“Come in,” he said, they ordered, “or we will kill your family.”

They took him to a cabin where several other young people were in the same situation, according to Marcos.

For months, he says he was made to be a foot soldier in a war he wanted no part in, before managing to escape with the help of a gang member who took pity of him.

Marcos spent months in a migrant shelter in the Mexican border city of Tijuana, waiting to present his asylum application to U.S. authorities, confident he could convince them he has what U.S. immigration courts call a “credible fear” of persecution or torture in Mexico. .

But he now believes President Trump’s sweeping executive orders on immigration and border security have ruined his chances of success.

“I hope they look at each person’s situation and take each case on its merits,” he said, “and that Mr. Trump’s heart softens to help those who really need it.”

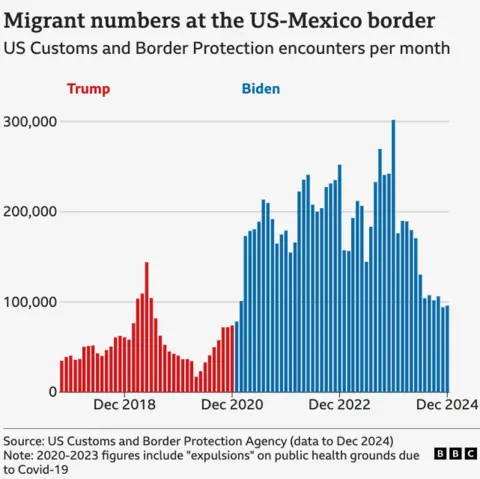

From the Oval Office Monday evening, hours after returning to the presidency, Trump signed a storm of orders aimed at fulfilling one of his main campaign promises: dramatically reducing illegal immigration and asylum applications to the American border.

Among these measures was the declaration of some drug cartels as terrorist organizations, paving the way for U.S. military action and expulsions.

The order perplexes Pastor Albert Rivera, director of a migrant shelter that mainly houses people fleeing cartel intimidation and death threats.

He says there is a contradiction at the heart of the decree.

“If we go from saying that these people are fleeing gangs to saying that they are now fleeing terrorists, that surely only strengthens their requests for asylum,” he says.

For Trump supporters across the border in Southern California, the need for these tough new measures is self-evident.

“It will be a relief,” Paula Whitsell, chair of the San Diego County Republican Party, said of the new president’s plan to launch what he calls “the largest deportation in American history.”

“Our system here in San Diego County is very stressed with the weight of all these people coming in, and we’re just not built for that. The county is not built to be able to handle that,” he said. -She.

She insists the measures are not fundamentally anti-immigration – “we are still a nation of immigrants” – but rather aim to deport undocumented criminals from the United States and dismantle the gangs that exploit the immigration routes. smuggling people across the border.

But for people waiting in Mexico, who say they have done nothing wrong and have legitimate claims for asylum, Trump’s orders have had swift and drastic consequences.

On the morning of the president’s swearing-in, about 60 migrants gathered at the Chaparral border crossing in Tijuana, waiting to speak to border guards about their asylum request. But they never got the chance, as Mexican authorities instead directed them to buses that would take them back to the shelters.

The CBP One app, a mobile application launched by the Biden administration and criticized by Trump during the election trial, had been shut down.

The application was the only legal avenue to seek asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border, and with all of its appointments removed, it was impossible to cross the border.

For some, it felt like the end of the road.

Oralia has lived with her two youngest children for seven months in a nylon tent just steps from the US border.

She says she is also fleeing threats from a cartel in Michoacán and that her 10-year-old son suffers from epilepsy. She said her hope was to get him medical care in a safe place in the United States.

But without the CBP One app, Oralia says she has little hope that her claim will ever be heard.

“We have no choice but to go back and trust God that nothing is happening,” she said.

A local migrant rights lawyer apparently advised him to wait and see how President Trump’s actions play out. But Oralia’s decision is made.

Her bags packed, the tent she inhabited for most of the last year is now vacant for the next family.

“This has all been so unfair,” she said, wiping away tears.

“Mexico receives its citizens without complaint, but the opposite does not work.

“I just hope God moves him (Trump) because there are a lot of families like ours.”