Medications given to people living with the virus make it non-transmissible during sexual intercourse. But pills called PrEP, for pre-exposure prophylaxis, are considered the missing link to ending HIV, because HIV-negative people who take them are nearly 100% protected against transmitting the virus. There’s even a new PrEP drug that researchers could soon administer twice a year – a discovery so important that the drug, called Lenacapavir and produced by Gilead Sciences, Inc., was Science Magazine’s Breakthrough of 2024.

But in Atlanta, gay black men and straight black women have been left behind, experts say. Black women now make up the second-largest group of people testing positive, surpassing infections among white gay men, traditionally one of the highest-risk groups.

Activists and researchers say the reasons are twofold: A large, uninsured population in Georgia means some cannot access medical care, while stigma among black Georgians has made HIV taboo. Until these problems are resolved, they say, the Peach State will struggle to bridge the gap between scientific advances and the mundane reality of treating at-risk patients in Atlanta.

The most exciting and novel dimension of lenacapavir is that it could eventually be administered as an annual injection, much like a vaccine, and could help end HIV in Atlanta and the United States.

In two Gilead-funded trials, one of which took place in Africa and the second at multiple sites in Asia, Latin America and the United States, including at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, the drug was found to be effective almost 100% as PrEP. The biannual injection test was so successful that Gilead quickly opened a second trial to evaluate whether Lenacapavir could be administered annually.

Dr. Colleen Kelley, co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research and leader of the Atlanta team that studied the effectiveness of lenacapavir, said wonder drugs only work if people can access them.

She cites another injectable PrEP drug called Apretude made by Viiv Healthcare. It is just as effective and has been approved by the FDA since 2021, but little used.

“People really want to take Apretude, but they don’t know how to get it,” she said. “Clinics had to learn to administer an injectable every two months. And insurance coverage remains very difficult. From a public health perspective, we’ve done a very poor job of providing access. This time, with Lenacapavir, we run this risk again.

Additionally, the government and pharmaceutical companies are not reaching people who could benefit from PrEP, said Leisha McKinley-Beach, a national HIV consultant and CEO of the Black Public Health Academy, which prepares black health workers. health department in leadership positions.

She said a free national PrEP program returned thousands of bottles of the medication to the drug company. “This proves to me that cost is not the major factor, but awareness, knowledge and connection to the community is,” she said.

According to a study by Harvard researchers, only 25% of the 1.2 million people in the United States who could benefit from PrEP were prescribed PrEP.

Nationally, about 1.2 million Americans are living with HIV and 31,800 have contracted the virus in 2022, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), a nonprofit organization that provides research, surveys and and health policy journalism.

In Georgia, 2,575 people were diagnosed with HIV in 2022 and 60,902 Georgians are living with HIV, according to the Ministry of Public Health.

Only Miami and Memphis trail Atlanta in new HIV infections, the AJC reported.

Joshua O’Neal of the Southeast HIV/STI Prevention Training Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said injectable PrEP products have been deployed in San Francisco and Seattle, but their Adoption in the South has been slow, with the exception of free PrEP. program at Grady Memorial Hospital.

“Many people are unable or unwilling to take daily medication,” he said. “That’s why these injectables are revolutionary.”

Most people living with HIV take medication in pill form daily, and many people on PrEP do the same. Both groups sometimes develop pill-related fatigue, said Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu of the Yale School of Medicine and principal investigator of the global Lenacapavir trials.

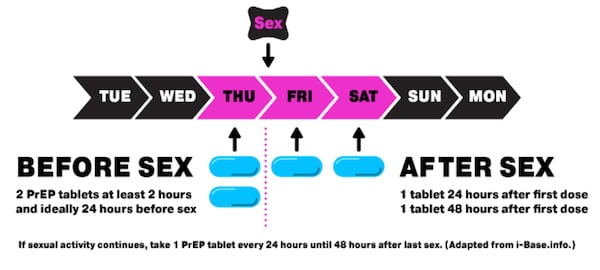

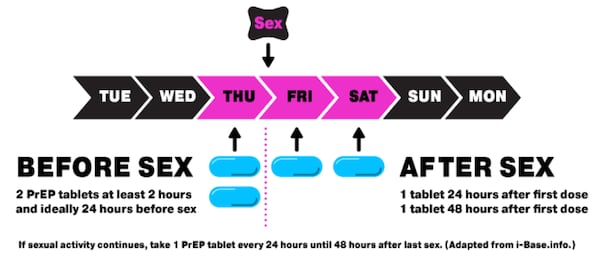

One solution to pill fatigue used in New York and many European countries is to prescribe PrEP “on demand” rather than daily. Activists attribute their success in reducing HIV infections among gay men, in part, to the flexibility afforded by on-demand dosing.

Credit: NYC.gov

Credit: NYC.gov

If access to medication is a bottleneck, stigma around HIV is a barrier that prevents black gay men and black women from achieving the decline in HIV infections seen among white gay men.

“The conversation in the black community is not as tolerant as it is in the white gay male community,” Traylor said. “I am one of two cisgender Black women speaking out about her diagnosis. I know thousands of women who feel that this is no one’s business. »

She said black women fear being fired from their jobs or losing their housing if they are associated with HIV, living with the virus or taking PrEP pills to prevent it.

Gilead’s Dr. Jared Baeten said the company’s research supports this.

“You may not want to bring home a bottle of HIV prevention pills that your aunt, partner or boyfriend might find out about,” he said. “People were asking for something discreet.”

Randevyn Pierre of Viiv Healthcare said people are also sometimes afraid to talk to their own doctor about PrEP for fear of judgment. “This disconnect due to stigma is a significant barrier to accessing PrEP that does not receive enough attention,” he said.

Southern HIV experts hope President Donald Trump will renew his commitment to his 2019 goal of ending new HIV infections in the United States within 10 years.

Kathie M. Hiers, CEO of AIDS Alabama, said her organization and others in the South will need help from the federal government and pharmaceutical companies to gain access to injectable HIV medications.

“I love the idea of long-acting injectables,” she said. “But the reality is we need to get all the right drugs at lower prices in states that don’t have Medicaid expansion.”

Additionally, people face barriers such as time constraints, reliable transportation and other logistical challenges to receiving injectable forms of PrEP from a provider or pharmacist, said Tristan Schukraft, CEO from MISTR, an online PrEP pharmacy that has a program to mail PrEP to uninsured patients for free. .

Yale’s Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu said Connecticut’s mandatory HIV testing for all patients seeking care in emergency rooms has helped the state detect HIV infections among young people who have not insurance.

Grady Memorial Hospital has an “opt-out” policy on HIV testing in its emergency room and 13 primary care clinics. But HIV testing in emergency rooms is not mandatory in Georgia, the Georgia Department of Public Health said.

Traylor says black women living with HIV could be the best advocates for PrEP and treatment if society stopped judging them.

“We need to destigmatize HIV so that people living with HIV actually feel comfortable talking about it,” she said.