Presenting to a Hong Kong hospital with complications due to urinary flow obstruction, an 84-year-old man left clinicians perplexed by a seemingly unrelated grayness on his skin, eyes and nails.

This unusual color was far from new. In fact, its slight ashen tint appeared five years ago.

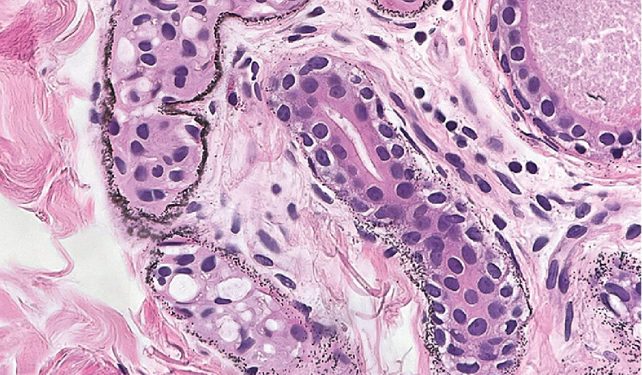

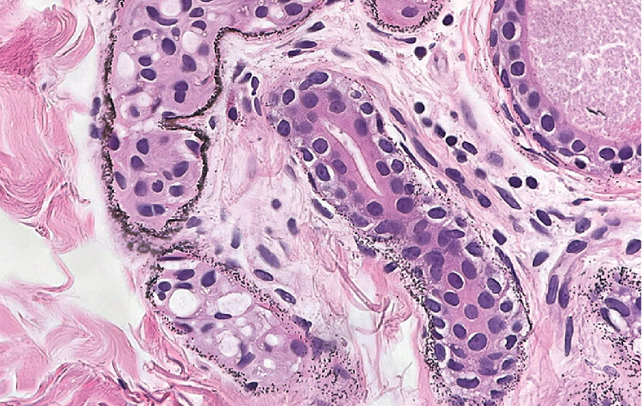

Blood tests quickly revealed the culprit: money. At concentrations more than 40 times those found in most individuals, the man’s body was positively saturated with the metal, causing it to turn into tiny oxidized granules just under his skin, in the membranes of his sweat glands, of its blood vessels and dermal fibers.

Known as argyria, systemic accumulation of silver in body tissues is rare, but far from unheard of. In extreme cases, individuals may be left with large areas of exposed skin that appear strikingly blue.

Historically, this disease affected artisans and miners who worked closely with the metal, but in a number of cases the element was absorbed through medications containing silver for its antimicrobial properties.

Colloidal silver continues to be used without scientific evidence supporting its effectiveness, with the United States Food and Drug Administration warning that the ingredient is not currently considered a safe or effective way to treat any disease or condition.

That’s not to say that silver “treatments” aren’t readily available around the world, often marketed as dietary supplements claiming to help expel toxins or boost the body’s defenses.

The metal is usually absorbed internally through the lungs, skin, or digestive system as a charged particle, depositing everywhere as it is transported throughout the body. Anywhere UV radiation from sunlight can reach, silver ions can pick up an electron and transform into a form that can react to form compounds that reflect a dull gray or blue color.

As the recently published case study reports, the 84-year-old was being treated for a benign prostate tumor, even though his only medication was a common antiandrogen called finasteride, which is not expected to contain anything even remotely money.

Having worked for years as a waiter, the patient had no obvious source of silver contamination in his workplace. Without any of her neighbors exhibiting similar changes in skin color, exposure in her home environment was also unlikely.

Fortunately, this condition is unlikely to have a significant impact on the patient’s long-term health. Aside from subtle cosmetic effects, silver accumulation is relatively benign except at the highest concentrations, at most potentially affecting the absorption of certain antibiotics and medications such as thyroxine.

That said, the man would have a hard time getting rid of his slate gray tone if he wanted to. There are currently no known measures to eliminate the accumulation of silver in the body.

For now, its provenance remains a mystery. However, with a diagnosis in their medical record, the patient’s doctors will no doubt be closely monitoring their Silver status for years to come.

This case study was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.