Being able to erase bad memories and traumatic flashbacks could help treat a host of mental health issues, and scientists have found a promising new approach to doing just that: weakening negative memories by reactivating positive ones.

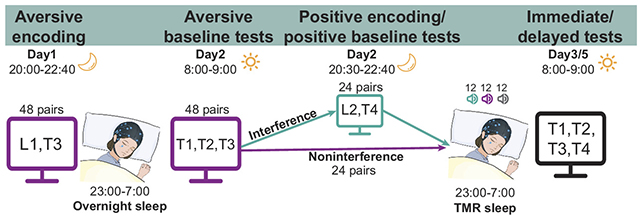

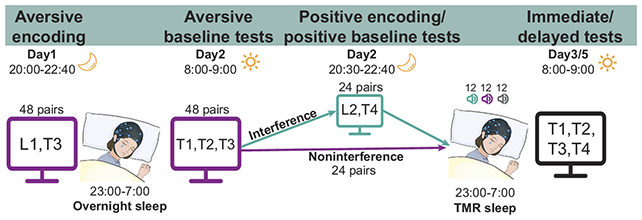

In a multi-day experiment, an international team of researchers asked 37 participants to associate random words with negative images, before attempting to reprogram half of these associations and “interfere” with the bad ones. memories.

“We found that this procedure weakened the recall of aversive memories and also increased involuntary intrusions of positive memories,” the researchers write in their published paper.

For the study, the team used established databases of images categorized as negative or positive – think human injuries or dangerous animals, compared to calm landscapes and smiling children.

On the first evening, memory exercises were used to get volunteers to associate negative images with nonsense words invented for the study. The next day, after a sleep intended to consolidate these memories, the researchers tried to associate half of the words with positive images in the participants’ minds.

During the second night of sleep, recordings of the nonsense words spoken were played, during the non-rapid eye movement (NREM) phase of sleep, known to be important for memory storage. Brain activity was monitored by electroencephalography.

Theta band activity in the brain, linked to emotional memory processing, was observed in response to audio memory cues, and was significantly increased. higher when positive cues were used.

Through questionnaires the next day and several days afterward, the researchers found that the volunteers were less able to recall negative memories that had been blurred with positive memories. Positive memories were more likely to come to mind than negative memories for these words, and were perceived with a more positive emotional bias.

“A non-invasive sleep intervention can thus modify aversive memories and affective responses,” write the researchers. “Overall, our findings may offer new insights relevant to the treatment of pathological or trauma-related memories.”

This research is in its early stages, and it is worth remembering that this was a tightly controlled laboratory experiment: this is good for relying on the accuracy of the results, but it does not reflect not exactly real-world thinking and the formation of positive or negative memories.

For example, the team says that seeing aversive images during a laboratory experiment would not have the same impact on memory formation as experiencing a traumatic event. The real thing might be harder to crush.

We know that the brain saves memories by briefly replaying them during sleep, and many studies have already examined how this process could be controlled to reinforce good memories or erase bad ones.

With so many variables at play – in terms of memory types, brain areas and sleep stages – it will take some time to understand exactly how memory editing might occur and how long the effects might last. However, this process of overwriting negative memories with positive ones seems promising.

“Our results open broad avenues for attempting to weaken aversive or traumatic memories,” the researchers write.

The research was published in PNAS.