The science of poop has yielded some fascinating results, but the latest installment of this beat may be the most astonishing yet. After decades of noticing, but generally not understanding, why reptiles “pee” in crystals, researchers finally believe they have the answer.

In a Journal of the American Chemical Society article published today, a team of organic chemists and herpetologists describe their investigation of urine crystals from more than 20 species of reptiles. Simply, reptiles pack excess nitrogen into tiny, textured spheres made of even smaller microcrystals. According to the researchers, these microscopic processes offer an evolutionary advantage to snakes, in addition to hinting at broader implications for human health.

The science of urine

The project began with a strange request that Jennifer Swift, a crystallographer at Georgetown University, received from herpetologist Gordon Schuett. Specifically, Schuett wanted to know why, even though he fed the reptiles in his care the same food and water, there was such strange variety in their pee crystals.

“What he observed was that of all the creatures he had in his museum, some of them were excreting urates that dried into a rock-hard mass, and some of them dried into something that looked like dust,” Swift, the lead author of the study, told Gizmodo in a phone call. “He asked me if I knew what was going on and I said, ‘I have no idea. Why don’t you send me some samples?”

So far, Swift has focused on the buildup of uric acid crystals in humans, which leads to serious health problems such as gout or kidney stones. Uric acid is one of the three main forms produced by animals as they break down excess nitrogen in their bodies. We mammals excrete excess nitrogen in the form of urea, which with plenty of water becomes urine.

On the other hand, reptiles and birds (both descendants of dinosaurs) excrete nitrogen in the form of solid uric acid, which researchers believe could have allowed animals to conserve water in dry climates.

Unraveling the mystery of “pee” crystals

Given the pesky implications of solid uric acid in humans, researchers gauged the potential benefits by learning how reptiles seemed to pass out these crystals without much trouble. But the few attempts to properly describe the molecular mechanisms at play have not been very successful, according to Swift.

“Because we also didn’t know what we were dealing with, we concocted literally every possible analysis method under the Sun and studied them in every possible direction,” she said.

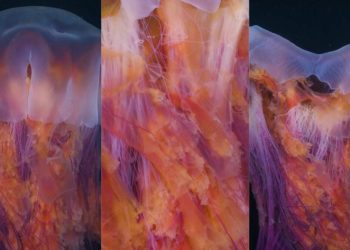

This included X-ray diffraction studies and high-resolution microscopy analysis of urates, or solid uric acid, from around 20 different reptile species, mainly snakes.

Their findings revealed the remarkably complex mechanism of nitrogen passage in reptiles. First, they produce tiny spheres of uric acid nanocrystals. Some species disposed of these microspheres directly, while others “recycled” the crystals to react with liquid ammonia, a deadly neurotoxin.

This allows the snakes to turn the ammonia into something solid, much less toxic particles that, when excreted, would be “dust blowing in the wind,” Swift explained. This potentially means that uric acid could play a protective role for snakes.

Of course, it’s still a big step to suggest that the same thing might apply to humans, Swift admitted. Still, it suggests there is still much to learn about uric acid’s role in biology, she said, adding: “Too much of it is a problem. Eliminating it completely is not an option.”

Regardless, the new findings demonstrate “the value of adopting biomimetic approaches to solving complex problems,” Swift added. “Millions of years of evolutionary history have allowed things to thrive in ways we wouldn’t normally think of. Nature has many remarkable processes that we simply don’t understand, because we haven’t taken the time to observe them.”