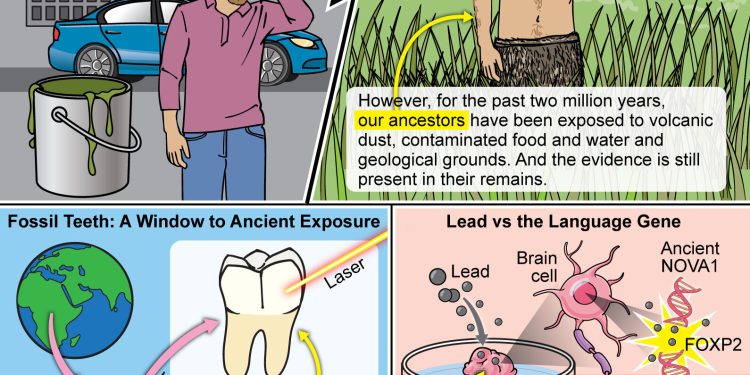

Infographics show the exposure of modern-day humans to that of our ancestors; how tooth fossils and brain tissue were analyzed for this study; how the modern NOVA1 gene might have protected modern humans from the adverse effects of lead. Credit: J Gregory, Mount Sinai Health System

An international study is changing the view that exposure to lead, a toxic metal, is largely a post-industrial phenomenon. Research reveals that our human ancestors were periodically exposed to lead for more than two million years and that this toxic metal may have influenced the evolution of hominid brains, their behavior and even the development of language.

In addition, the study, published in Scientific advances– adds a piece to the puzzle of how humans surpassed their cousins, the Neanderthals. Brain organoid models with Neanderthal genetics were more sensitive to the impacts of lead than human brains, suggesting that lead exposure was more harmful to Neanderthals.

Led by researchers from the Geoarchaeology and Archaeometry Research Group (GARG) at Southern Cross University (Australia), the Department of Environmental Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital (New York, USA), and the University of California San Diego School of Medicine (UCSD, USA), the research combined new fossil geochemistry, cutting-edge experiments on brain organoids and pioneering evolutionary genetics to uncover a surprising story about the role of lead in human history.

A toxic thread through human evolution

Until now, scientists believed that lead exposure was largely a modern phenomenon, linked to human activities such as mining, smelting and the use of leaded gasoline and paint. By analyzing 51 fossil teeth from hominid and great ape species, including Australopithecus africanus, Paranthropus Robustus, early Homo, Neanderthal and Homo sapiens, the team discovered clear chemical signatures of intermittent lead exposure dating back almost two million years.

Using high-precision laser ablation geochemistry at Southern Cross University’s GARG facility (located in Lismore, New South Wales) and the state-of-the-art Exposomics facility at Mount Sinai, researchers discovered distinctive ‘lead bands’ in teeth, formed during childhood as enamel and dentin developed. These bands reveal repeated episodes of lead absorption from both environmental sources (such as contaminated water, soil, or volcanic activity) and from the body’s bone stores, released during stress or disease.

“Our data shows that lead exposure was not just a product of the industrial revolution: it was part of our evolutionary landscape,” said Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau, head of the GARG research group at Southern Cross University.

“This means that our ancestors’ brains developed under the influence of a powerful toxic metal, which may have shaped their social behavior and cognitive abilities over millennia.”

Using human brain organoids (miniature models of the brain grown in the laboratory), the team compared the effects of lead on two versions of a key developmental gene called NOVA1, a gene known to orchestrate gene expression during lead exposure during neurodevelopment. The modern human version of NOVA1 is different from that found in Neanderthals and other extinct hominids. Credit: University of California, San Diego

From fossils to function: lead and the language gene

The team also turned to the laboratory to explore how this ancient exposure might have affected brain development. Using human brain organoids, miniature models of the brain grown in the laboratory, they compared the effects of lead on two versions of a key developmental gene called NOVA1, a gene known to orchestrate gene expression during lead exposure during neurodevelopment. The modern human version of NOVA1 is different from that found in Neanderthals and other extinct hominids, but until now, scientists did not know why this change evolved.

When organoids carrying the archaic NOVA1 variant were exposed to lead, they showed marked disruptions in the activity of FOXP2-expressing neurons in the cortex and thalamus, brain regions essential for speech and language development. This effect was much less pronounced in organoids with the modern NOVA1 variant.

“These results suggest that our NOVA1 variant may have provided protection against the harmful neurological effects of lead,” said Professor Alysson Muotri, professor of pediatrics/cellular and molecular medicine and director of the Orbital Integrated Space Stem Cell Research Center at the UC San Diego Sanford Stem Cell Institute.

“This is an extraordinary example of how an environmental pressure, in this case lead toxicity, could have driven genetic changes that improved survival and our ability to communicate using language, but now also influence our vulnerability to modern lead exposure.”

Laboratory experiments with brain organoids carrying modern or archaic NOVA1 genes examined the effects of lead on brain development, with a focus on FOXP2, a gene central to speech and language. Credit: University of California, San Diego

Genetics, neurotoxins and the creation of modern man

Genetic and proteomic analyzes in this study revealed that lead exposure in archaic variant organoids disrupted pathways involved in neurodevelopment, social behavior, and communication. The altered FOXP2 activity in particular indicates a possible link between ancient lead exposure and the evolutionary refinement of linguistic abilities in modern humans.

“This study shows how our environmental exposures have shaped our evolution,” said Professor Manish Arora, professor and vice chair of environmental medicine.

“From the perspective of interspecies competition, the observation that toxic exposures can provide an overall survival advantage offers a new paradigm for environmental medicine to examine the evolutionary roots of disorders related to environmental exposures.”

Modern lessons from an ancient problem

Although lead exposure today is primarily due to human industry, it remains a serious global health problem, particularly for children. The findings highlight how environmental toxins and human biology are deeply linked and warn that our vulnerability to lead may be a legacy from our past.

“Our work not only rewrites the history of lead exposure,” added Professor Joannes-Boyau, “it also reminds us that the interaction between our genes and the environment has shaped our species for millions of years and continues to do so.”

The study analyzed fossil teeth from Africa, Asia, Europe and Oceania, using advanced geochemical mapping to identify patterns of lead exposure in children. Laboratory experiments with brain organoids carrying modern or archaic NOVA1 genes examined the effects of lead on brain development, with a focus on FOXP2, a gene central to speech and language. Genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data were integrated to provide a comprehensive picture of how lead may have influenced the evolution of hominid social behavior and cognition.

More information:

Impact of intermittent exposure to lead on the evolution of the hominid brain, Scientific advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr1524

Provided by Southern Cross University

Quote: Ancient lead exposure may have shaped human brain evolution (October 15, 2025) retrieved October 16, 2025 from https://phys.org/news/2025-10-ancient-exposure-evolution-human-brain.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.