Scientists analyzing 1,300-year-old human feces from the Cave of Dead Children in Mexico have discovered that people often suffered from serious intestinal infections more than a millennium ago.

“Working with these ancient samples was like opening a biological time capsule, each revealing insights into human health and daily life,” said the study’s lead author. Drew Caponeassistant professor of environmental health at Indiana University, said in a statement.

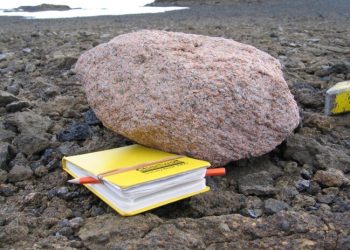

Capone and his colleagues used molecular analysis techniques to study 10 ancient samples of dried feces – also called paleofeces – found in a cave in Mexico’s Rio Zape Valley, just north of the city of Durango in northwestern Mexico, dating from 725 to 920 AD. The researchers published their results on Wednesday October 22 in the journal PLOS One.

In the late 1950s, archaeologists excavated the Cave of Dead Children and recovered human and non-human paleofeces, plant remains, and animal and human bones from a large trash pile. The cave was used by people of the prehistoric Loma San Gabriel culture, who practiced small-scale agriculture, produced unique ceramics, lived in small villages, and occasionally practiced child sacrifice. Archaeologists named the cave after the skeletons of children found there.

Previous studies of the cave’s paleofeces revealed the presence of hookworm, whipworm And pinworm eggs, suggesting that the people who deposited their feces in the cave were infected with various parasites.

In the new study, scientists used cutting-edge molecular techniques to detect additional microbes in paleofeces from 10 “distinct defecation events” in an effort to expand their understanding of the disease burden among the Loma people. “There is a lot of potential in applying modern molecular methods to inform studies of the past,” study co-author Joe Brownprofessor of environmental sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in the release.

The researchers extracted DNA from the 10 paleofeces samples, then used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the DNA of microbes present in the stool. Each sample contained at least one gut pathogen or microbe, and the two most common were the intestinal parasite. Blastocystwhich can cause gastrointestinal problems and several strains of the bacteria E.coliwhich were found in 70% of the samples. Pinworms have also been identified as well as Shigella And Giardiawhich cause intestinal diseases.

The high number of microbes found in the paleofeces “suggests that poor sanitation within the Loma San Gabriel culture between 600 and 800 CE led to exposure to fecal waste in the environment,” the researchers wrote in the study. People likely ingested the microbes through drinking water, soil or food contaminated with feces, the team added.

Although these pathogen-associated genes persisted in paleofeces for 1,300 years, there may have been even more pathogens in the samples that have since decayed and are no longer detectable, the researchers noted in the study.

Yet the new analysis revealed DNA from pathogens not previously found in paleofeces, including Blastocyst And Shigella.

“Applying these methods to other ancient samples offers the potential to expand our understanding of how ancient people lived and what pathogens may have impacted their health,” the researchers wrote.